See explanation below

Origin of life

Summary

The question of the origin of life involving the storage of biochemical information represents a problem that, despite a wide range of approaches in the natural sciences, has so far remained unresolved. One reason may be that the environmental conditions required for this process have not yet been correctly identified. From a geological perspective, the protected environment of the continental crust offers ideal conditions. Within this setting, entirely new possibilities arise for identifying processes that may have been decisive for the emergence of the first cell.

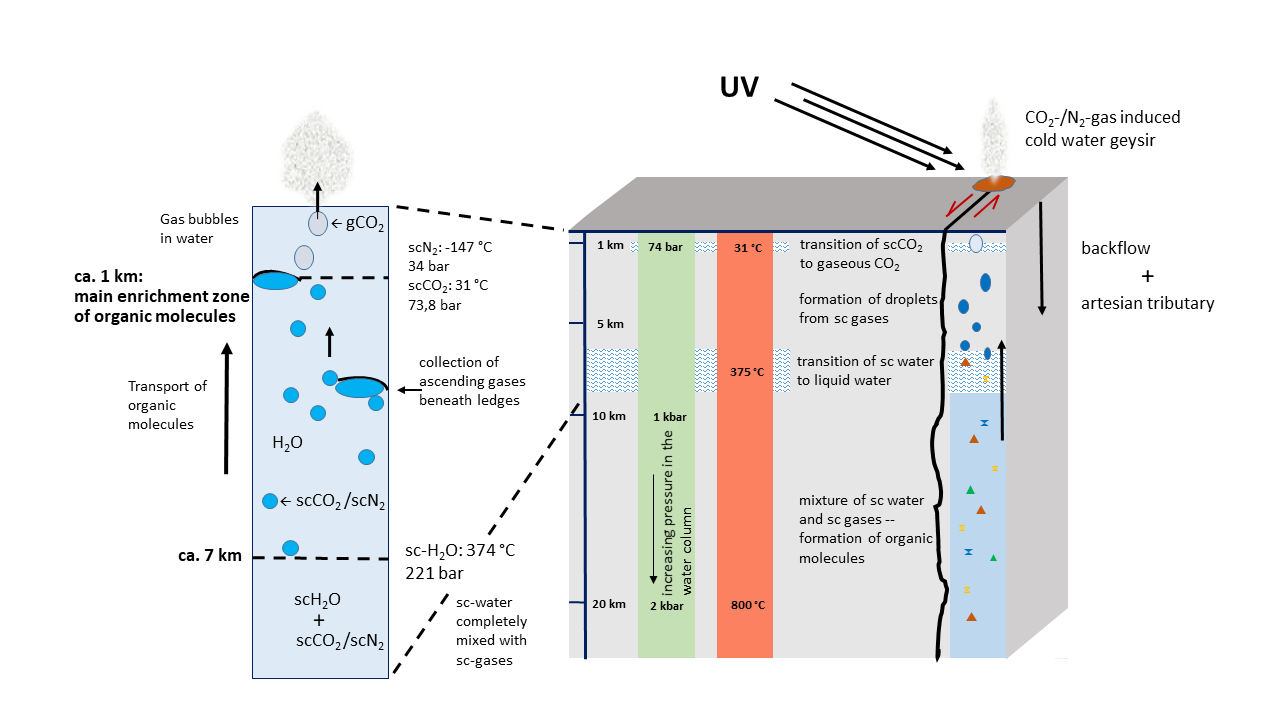

Against this background, a theory was developed proposing that cellular life began with a pressure-controlled cycle at the interface of supercritical gases. The associated storage of peptide sequences in RNA occurred at crustal depths of approximately 400 to 1,000 meters within cavities of varying size. This cycle could operate within an open system linked to gas-permeable tectonic fracture zones containing high proportions of CO₂ and N₂ derived from the Earth’s mantle. The formation of peptides and vesicles in supercritical CO₂/N₂, as well as the chemical evolution of peptides, has already been demonstrated for the upper continental crust.

Further considerations address the interactions of vesicles with catalytic peptides and the formation of a proto-tRNA. Hydrophobic amino acids accumulate within the vesicle membrane, with their position in the membrane depending on their degree of hydrophobicity. With adenine at the tip of the acceptor arm of the proto-tRNA, membrane penetration becomes possible, allowing linkage to an amino acid upon contact. The depth of penetration is controlled by the hydrophobicity of the opposing anticodon. Separation of proto-tRNAs into single strands generates templates that enable the linkage of amino acids into short peptides. Upon vesicle disintegration during each cycle, the reaction products are released back into the cavities, where they accumulate. As a result, with each new cycle the vesicles take up an increasingly complex molecular mixture. At a certain point, the molecular composition reached the threshold required for the autonomous development of the first cell.

To get started:

From star gas to the first cell - The origin of life in the continental crust (in German) May 28, 2024

Public evening lecture as part of the lecture series "Discovering origins: A journey from the beginnings of the earth to the emergence of humanity" by Professor Dr. Ulrich Schreiber (Duisburg-Essen)

https://www.wiko-greifswald.de/mediathek/beitrag/n/aus-dem-sternengas-zur-ersten-zelle-der-ursprung-des-lebens-in-der-kontinentalen-kruste-196975/

To investigate the cause of ebb and flow, it is not beneficial to merely observe the ocean.

The most precise examination of a rocket or an airplane provides no indication of the development of the earliest human tools, such as hand axes or knives. Yet, these tools form the foundation of the technological revolution.

How and where did life originate?

The continental crust as a model space for the formation of the first cell

Ulrich C. Schreiber; Bonn, November 2022

May 2024

Update: December 2025

The all-encompassing question

How could an organic chemistry arise from inorganic substances, from gases, water and rocks, from which a biological information system developed? The storage of information about the blueprints of the cells, with all their biochemical instruments and coordinated reaction processes, represents the absolute basis of life. And how did life manage to assert itself against the ubiquitous increase in entropy and to build up orderly structures? These questions are among the greatest in science, apart from those concerning the actual origin of the universe.

First things first – The environment

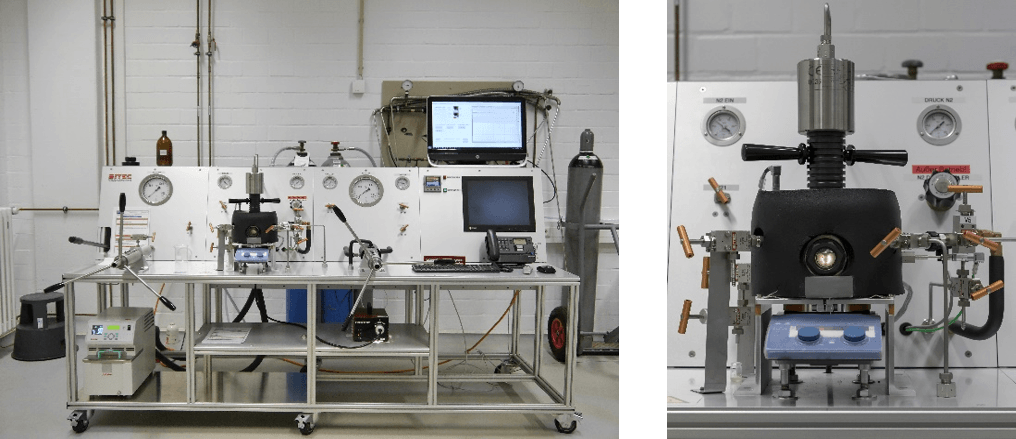

At the University of Duisburg-Essen, together with the physical chemist Prof. Dr. Christian Mayer has developed a model in recent years that offers a scientific explanation for the first steps on the way to life [1]. The model is supported by experiments with a high-pressure cell (Fig. 1), which simulates realistic conditions as they still exist today. A more detailed understanding of the origin of the molecule, its concentration, questions of energy and entropy, and membrane formation has already been achieved [2].

Fig. 1 left: high pressure system, right: detail with insulated pressure cell (50 ml)

What is it about?

The conditions of the young earth and the conditions for the emergence of life are largely in the dark due to the great temporal distance to today. A lack of boundary conditions prevents a clear delimitation of the possible processes, so that only narrowly limited statements on individual reactions could be made in a large number of precursor models. All localities on the earth's surface, from the deep sea to icy regions to shallow ponds, were discussed as possible environments. Due to criticism of the models and the lack of plausible alternatives, there have recently been proposals to include extraterrestrial regions such as Mars or meteorites in space as a whole.

Fig. 2 Bedrock outcrop in northern Norway on the way to Kirkenes, near the border with Finland - Faults and fissures in the rock are filled by granitic magmas (pink veins) or hydrothermally formed quartz (white veins).

The continental crust, which 4 billion years ago had grown to 25% of today's size [3], was only examined more closely by the Essen research group [1]. It differs from oceanic crust in that it is less dense and less warm, thicker, and has a more diverse mineralogical and chemical composition. If you look closely, the conditions within the continental crust are almost ideal for a start-up phase. By analyzing the framework conditions there, a large number of new approaches could be found that help to solve problems that are considered unsolvable in other models. The starting point is deep-reaching tectonic fault zones that are in contact with the earth's mantle. They are comparable to the San Andreas Fault or the Bavarian Pfahl fault in the Bavarian Forest, which is more than 200 km long and has been an active fault zone for more than 250 million years. Water, CO2 and other gases, which contain all the necessary substances for the formation of organic chemical molecules, rise from the depths, as is still the case today in the Eifel, for example.

One of the strongest arguments for examining this region more closely with regard to the origin of life is the CO2, which at a depth of approx. 800 meters undergoes a phase change from supercritical gas (scCO2, as it exists at depth) to gaseous CO2 (subcritical, gCO2, for the upper range) (critical point of the pure gas at 31 °C and 73.8 bar). In the supercritical state, scCO2 takes on the properties of both a liquid in which substances are dissolved and of a gas phase. Many chemical reactions can take place in scCO2 that are not possible in water. It acts like an organic solvent and greatly expands the number of possible chemical formation reactions. It also forms interfaces with water where special reactions can take place.

Due to a drop in pressure, the scCO2 changes to gCO2 in the border region from approx. 1000 m to 800 m depth (the pressure varies here due to the number of gas bubbles in the overlying water column). As a result, vesicles form with the formation of a double-layer membrane, which can be regarded as the precursor of the cell (see below). In addition to CO2, nitrogen (N2) is another gas that was pumped from the mantle into the atmosphere in large quantities and must have appeared in the upwelling channels of the fault zones in mixtures with CO2 or in pure form. The physical data (critical point of pure N2 gas at −146.9 °C and 33.96 bar) show that the supercritical state already occurs at about 350 m depth in an open water column (again depending on the number of gas bubbles in the supernatant water ). This has advantages for some chemical reactions, since the pH value is higher and more in the neutral range.

Molecular fossils from nature

Basic steps on the way to a cell can already be documented in the laboratory [4]. This includes the formation of vesicles, which can be considered the first cell-like structures, and the linking of amino acids to form longer chains, which are the basis for the formation of complex molecules such as proteins and enzymes. What is particularly attractive for the model is the fact that the conditions for the emergence of life in hydrothermal vein rocks from the early days of the Earth have been partially documented. A large number of organic substances from this period are hidden in tiny liquid inclusions, such as those found by us in archaic vein quartz from Australia and from corresponding boulders in conglomerates (quartz crystallizes under hydrothermal conditions in fault zones) [5]. They were trapped and conserved billions of years ago during crystal formation. They help us to approximate the conditions for the laboratory tests to reality. The complex analysis was possible through the cooperation of the laboratories from Heidelberg (Heinz F. Schöler and Frank Keppler with Ines Mulder, Tobias Sattler and Markus Greule) and Essen (Christian Mayer with Maria Davila and Oliver J. Schmitz with Pia Rosendahl and Amela Bronja).

Fig. 3 Schematic Block Profile of Early Continental Crust. The average thickness of continental crust today is 30 km. Here, it is assumed to be lower. Simultaneously, the temperature must have been higher but could have been cooled in the upper portion by artesian waters.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Fig. 4 Conglomerate in the Jack Hills, Western Australia, from which hydrothermal quartz boulders were analyzed. The oldest zircons to date have been found in the rock (> 4 billion years).

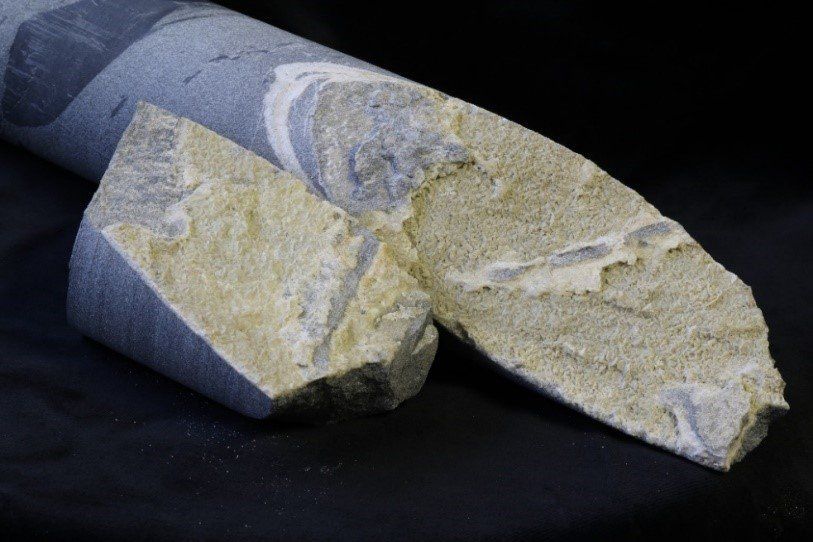

Even in almost recent mineral inclusions, the same series of molecules (aldehydes) can be found in the appropriate environment, which were formed inorganically from the gas components of the crust. For example, calcite could be extracted from a drill core from the CO2-carrying fissures of the young Wehr volcano (west of Lacher See) at a depth of almost 1000 m, which shows a comparable chemistry to archaic quartz from Australia. The analyzes were mainly carried out in cooperation with Prof. Oliver J. Schmitz in the chemistry department of the university [6].

Fig. 5 Calcite-mineralized fissure in the drill core from the Wehrer Kessel (approx. 960 m depth), last eruption approx. 150,000 years ago, cracking in the rock due to volcanic tectonics, subsequently mineralized with calcite minerals, in which there are fluid inclusions with complex organic chemistry. Photo: Prof. Dr. O. J. Schmitz

However, research into the development of the biological information system in DNA or in the presumed precursor of RNA poses a particular challenge. The physicochemical conditions in the continental crust also appear to have been favorable for this process. The first signs of a solution are already emerging.

Fundamentals of the origin of life

Since molecular tools such as enzymes did not exist at the beginning, the first steps towards life must have been purely physical or physicochemical. Thus, the formation of some of the components required for the cell can be explained by processes that are used daily in technical chemistry today. These include methods like the Fischer-Tropsch synthesis, which yields long-chain hydrocarbons, and the Haber-Bosch synthesis, producing ammonia (NH3) from N2 and H2. The requisite pressure-temperature conditions are present in the crust, along with the necessary raw materials. Furthermore, consideration must be given to the conditions and processes that were present or occurred overall, shaping the development of life within its emergence environment.

The Increase in Entropy as a Prerequisite for the Origin of Life:

- The linking of molecules, such as two amino acids, generates more order than previously existed in the system under consideration. Chemical reactions (e.g., condensation reactions) occur only if a higher degree of disorder is simultaneously formed, thus increasing entropy overall. For instance, heat may be generated in a test tube by a reaction, dissipating outwardly, thereby increasing entropy. Therefore, the increase in entropy (often described as an increase in disorder) must have been ensured throughout the course of life's development during reactions.

The transition from supercritical CO2 (sCO2) to gas (gCO2) at approximately 800 - 1000 m depth is associated with a significant increase in entropy.

- Typically, chemical reactions require energy to proceed, which must have been available to the necessary extent.

Heat energy, potential energy (from the rise of gases), and chemical energy (partially from piezoelectric voltage buildup due to seismic activity) were available in the crust. Additionally, there was a non-negligible radiation component due to the decay of radioactive elements in minerals.

- The environment had to remain stable over very long periods, protected from UV radiation, solar wind, weathering, meteorite impacts, and erosion. Hundreds of millions of years were necessary.

Fault zones such as the San Andreas Fault or the Bayerischer Pfahl attained this lifespan.

- The system had to remain open and out of equilibrium, allowing for the influx and efflux of substances. Molecules were consumed, but "unusable" molecules or reaction products could not clog the system (the problem of tar formation).

Water and molecules were transported toward the surface by rising gases in the faults.

- Cyclical changes in physical conditions must have prevailed. Cyclical conditions are more conducive to chemical evolution than sporadic events.

Cyclical pressure fluctuations occurred at the transition zone from scCO2 to gCO2 due to eruptions of cold-water geysers or significantly stronger Earth tides back then (the Moon was much closer to Earth), resulting in constant changes in conditions.

- Raw materials for the formation of organic molecules and necessary elements (metals, metalloids) had to be abundant.

Unlimited resources were available due to the influx of gases (CO2, N2, H2, H2S, etc.) from the mantle and the alteration of rocks, releasing phosphate and metals/metalloids.

- The formation of various organic molecules required different pressure-temperature (pT) conditions.

A transport system for bringing together the different molecular building blocks formed in various locations was one of the crucial requirements. Water and molecules formed at different depths were transported toward the surface by rising gases in the faults.

- Condensation reactions, such as the formation of a peptide from amino acids, can only occur if the water molecule produced during the reaction is removed.

In water (e.g., the cell), this is only possible with enzymes, thus in the early phase, a non-polar solvent is best suited. For example, in gas-rich fault zones, scCO2 or supercritical N2 serves as a non-polar solvent.

- Inorganic catalysts were likely required for the formation of RNA (tRNA) as the first carriers of information. Clay minerals have been discussed as potential catalysts based on laboratory studies.

Clay minerals form not only through weathering of surface rocks but also through alteration of rock-forming minerals in the Earth's crust by acidic waters in the faults.

- A fundamental problem on early Earth was the formation of a large number of different organic molecules, including in fault zones of the continental crust. There was essentially a molecular chaos from which specific molecules could not yet be filtered out by "biochemical tools." Only physical or physicochemical processes were available for pre-sorting:

Flow processes in the water-filled faults of the continental crust due to rising scCO2 gases (or gases in the uppermost 800 meters).

Surface effects allowing for the attachment of specific molecules to changing mineral surfaces (rock-forming minerals, vein ores such as lead-zinc or iron-sulfide ores, quartz, clay minerals) during ascent.

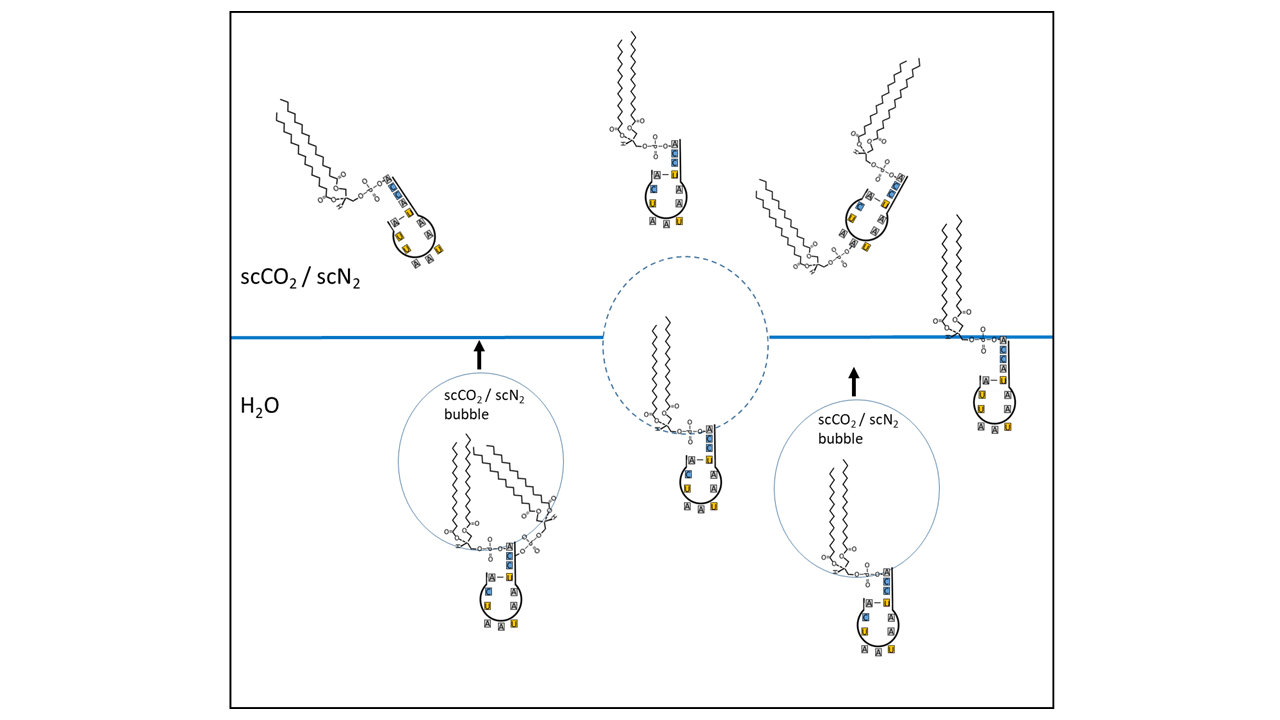

Flotation by scCO2/scN2 bubbles, which directly captured non-polar molecules or deposited certain amphiphiles on the bubble surface, acting as collector molecules for specific RNA molecules, for instance.

Example: Molecular Separation Analogous to Technical Chromatographic Processes

Within the fracture zones, fluid flow provides all prerequisites for separation processes from mixtures of organic molecules. The conditions are analogous to chromatographic analytical and separation techniques, in which a dynamic interplay between a solvent and a stationary phase leads to the separation of a wide variety of molecules. Fractures and fault surfaces in the continental crust exhibit cross-sectional dimensions ranging from capillary scale to several tens of centimeters. These dimensions are comparable to those employed in technical separation processes.

Of particular interest is the separation process when the mobile phase is in a supercritical state. Corresponding effects in the continental crust are directly comparable to supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC), which is predominantly conducted using supercritical CO₂. In this technique, silica gels are used as the stationary phase. Silica gels are characteristic of deeper-reaching fault zones; from them, the vein mineral quartz is formed, which frequently lines fracture surfaces and constitutes the basis of quartz veins.

There are also processes such as the simulated moving bed (SMB) process, in which the stationary phase moves counter to the substances being separated. This would be the case if silica gels were transported upward within the fluid flow of fracture zones. SMB processes are used, for example, in the pharmaceutical industry when large quantities of molecules with different chiralities must be separated. They are also employed for the industrial-scale purification of fructose. This may underlie the preferential use of ribose during RNA formation in hydrothermal fracture systems of the crust. Through chromatographic separation of mixtures of various sugars, ribose would, in this scenario, have been most strongly enriched and thus most readily available.

Zone of Molecular Enrichment

In the transition zone between approximately 1,000 m and 800 m depth, the gases undergo a phase transition from the supercritical to the subcritical (gaseous) state (for pure N₂ systems, this transition occurs at shallower depths). Due to pressure fluctuations—for example during cold-water geyser eruptions (CO₂/N₂-driven eruptions)—the depth of the transition to the subcritical gas phase varies over several tens of meters. The consequence is precipitation of organic molecules, because the newly forming subcritical gas can no longer keep these molecules in solution. As a result, an enrichment horizon develops in which concentrations become sufficiently high to favor chemical reactions.

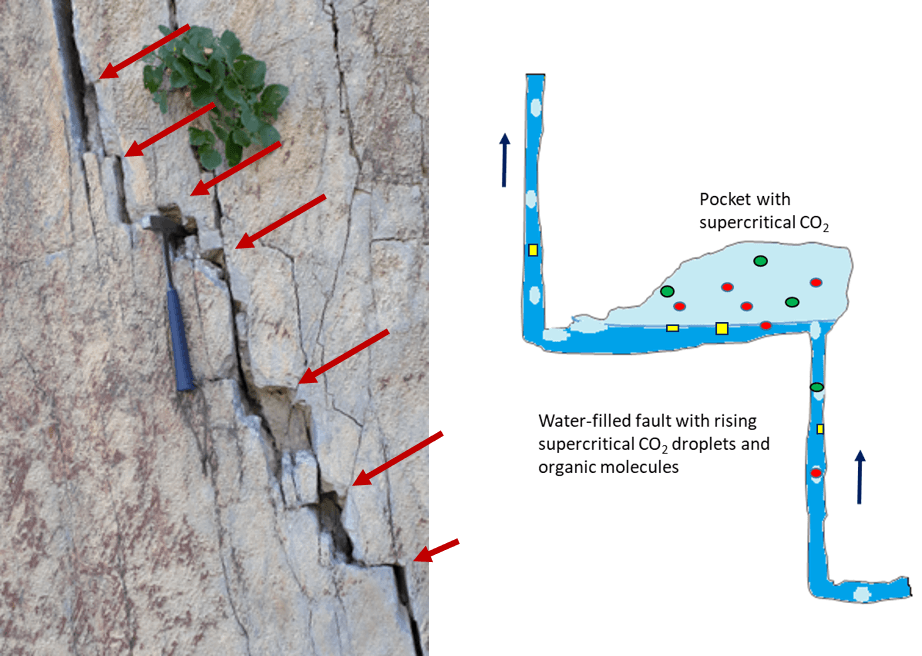

Fig. 6 Example of the conditions in a fault. The arrows point to traps for rising gases in case the system is filled with water in the crust (left - photo: Dr. Frederik Kirst). At greater depths below about 800 m, scCO2 collects under the ledges. Here, non-polar molecules can be enriched in the supercritical gas and react with each other (sketch on the right).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

RNA

The formation of RNA (as a precursor to DNA) is among the most important prerequisites for the development of an organic–chemical information system. Conditions within fracture zones were favorable for this process due to the availability of organic bases, the sugar ribose, and phosphate released from the dissolution of apatite minerals [9]. However, this environment did not yield exclusively the molecules present in modern RNA. There was certainly a wide variety of different sugars, each also occurring in both D- and L-chiral forms. Alteration of crustal rocks led, in various sections of fracture surfaces, to coatings of clay minerals. These likely acted as catalysts that directed the linkage of nucleotides into longer RNA chains [8].

As a result, the RNAs formed could vary greatly due to differences in sugars and/or bases. It is therefore necessary to identify processes that, without the aid of modern biochemical catalysts, led to the particular type of RNA that ultimately governed subsequent steps on the path to the first cell. One possible basis for this selection toward the RNA form observed today may have been the SFB and SMC processes described above, which regulated the availability of relevant molecules in terms of both quality and quantity through chromatographic separation steps.

During the formation of longer RNA strands, entanglement occurs rapidly because complementary regions associate and partially form double-stranded segments [10]. This prevents copying by the attachment of free nucleotides, representing a core problem of the RNA world hypothesis. However, double strands can be melted by increasing temperature and subsequently become available for duplication upon cooling. The conditions within fracture zones provide optimal settings for RNA copying. At depths of approximately 1,000 m, temperatures may have been slightly above 50 °C due to the influx of surface water. The transition of supercritical CO₂ to the gaseous phase during a geyser eruption leads to cooling as a result of gas expansion (Joule–Thomson effect).

The reverse process—gas compression—is associated with a temperature increase. In this case, temperatures well above 60 °C can be reached, which are necessary to separate RNA double strands. Additional temperature fluctuations arise from the inflow of hotter water from greater depths and the subsequent return flow of cooler water from shallower levels after the eruption ceases. Upon cooling, the phase of complementary nucleotide attachment begins. If sufficient building blocks are available, RNA strands can be copied during each eruption cycle. Similar processes can occur with supercritical nitrogen (scN₂) at shallower depths and correspondingly lower background temperatures and higher pH values.

If environmental conditions are suitable for RNA formation, this does not automatically imply the establishment of an information system. RNA strands that form exhibit different lengths and are rapidly cleaved into shorter fragments by hydrolysis. Hydrolysis of RNA strands is minimal in acidic environments with pH values between 3 and 4, as also present in fracture-zone fluids at depth [11], representing the range of greatest stability. Even after coarse preselection, a very large number of different molecules remain, only some of which are required for subsequent steps. This means that for every emergence of more complex building blocks from simpler precursor molecules that persist in the system, an advantage in stability must have existed. This is the essence of chemical evolution, and its causes are always physicochemical principles underlying molecular stability.

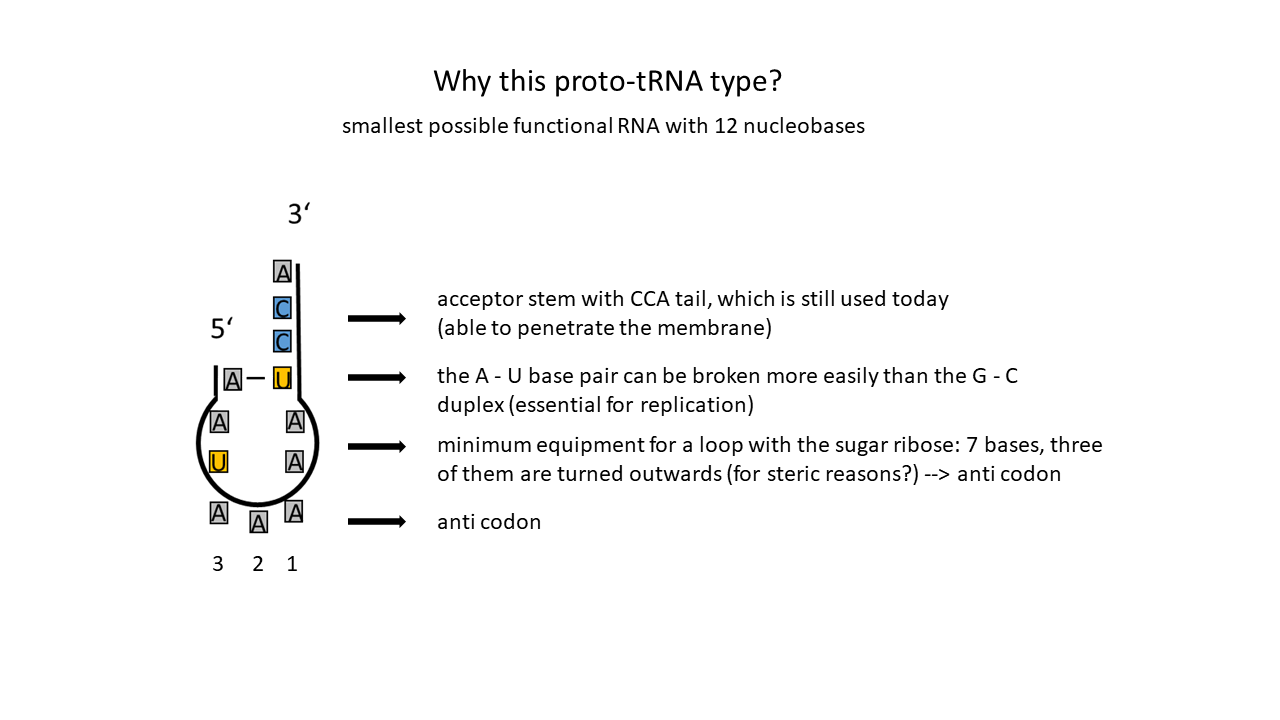

Beyond a certain length, there is a high probability that the first and last thirds of an RNA strand contain regions with complementary bases. This implies that upon bending, the bases of both thirds face each other and can form a connection via base pairing, as in a DNA double strand (adenine A pairs with uracil U, cytosine C with guanine G). The middle third forms a loop, whose size depends on its length. If sufficiently large, all nucleobases are oriented inward. If the length reaches a critical size for loop formation such that only a single base pair is available to stabilize the loop, the loop can form only if three of the bases point outward (through rotation within the strand). In this way, an anticodon is generated that can interact with three complementary bases. Today, this anticodon is located at one end of tRNA (transfer RNA), which in cells—albeit in a much more complex form—acts as the intermediary between a specific amino acid and an information code.

If this early RNA with an anticodon became established as a proto-tRNA, the question arises as to how large and how simple its overall structure may have been. It certainly did not exhibit the complexity observed today. It must have possessed a minimal strand length combined with specific structural features. This consideration is based on the fact that short RNA strands are more frequently formed and more stable than longer ones. In addition, a single base pair can be separated more easily to enable the copying of the strand—necessary for continued persistence—than a larger number of base pairs.

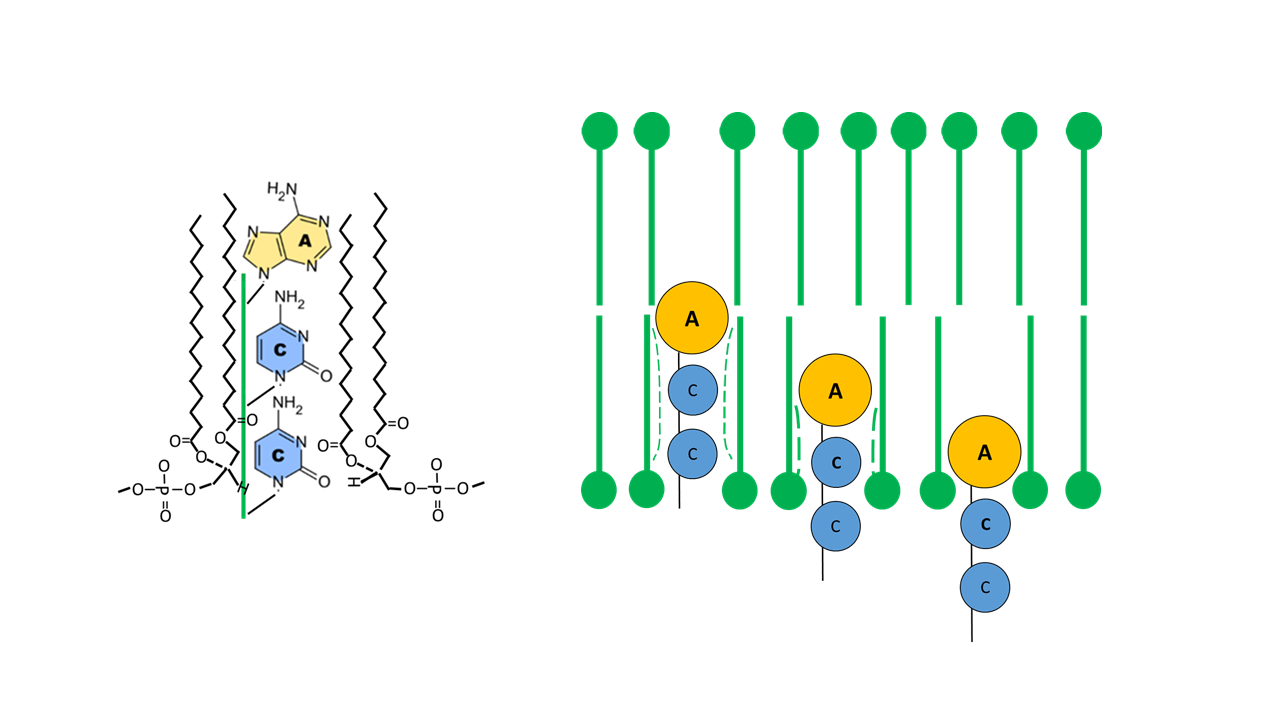

In addition to the loop with the anticodon and the single base pair, one essential component remains, referred to above as a “special feature”: a single-stranded section at the opposite end to which an amino acid can be attached (see below). This yields a prototype of a simple proto-tRNA with a minimal length of twelve nucleotides. It is depicted in Fig. 7 and contains only a single base pair.

Fig. 7 Possible Proto-tRNA: Shortest possible RNA strand forming only one base pair and an extended single strand, with its last three bases always being C, C, A (Cytosine, Cytosine, Adenine). Three bases are positioned in the loop (here AAA; outward orientation due to steric constraints when using the sugar ribose) in the anticodon; an outward-facing position requires a rotation within the strand), which can be complemented by complementary free bases. These form the codon, a triplet code composed of four different RNA bases that currently constitute RNA. (U = Uracil)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This immediately raises the question of why ribose, a five-carbon sugar (a pentose), forms the backbone of RNA, rather than one of the other pentoses or even the hexoses, which are six-carbon sugars. In laboratory experiments, such alternative nucleotide chains can indeed be synthesized. The various sugars must ultimately have been present in large diversity within the environments considered here, since their formation is not selective for a single type. On this basis, there were presumably a number of other RNA strand types that incorporated different sugars, which were likewise chiral and therefore existed in two distinct handednesses.

Which selection processes, then, could have led to the choice of ribose? Stability criteria or simple abundance—arising from the separation processes described above—certainly must be considered. However, another cause may have been decisive, arising from the tight loop of the proto-tRNA strand described above. The three bases that are forced to point outward for steric reasons must, in combination with the sugar molecules, have been arranged such that they could be read as a single unit, as a triplet block. Any alternative configuration that did not ensure this property would not have allowed further evolutionary progress.

It therefore becomes necessary to compare whether alternative sugars—both other pentoses and hexoses, as well as others—can yield an RNA loop configuration that includes an outward-facing, “readable” triplet block. Any arrangement of bases that impairs or prevents such readability would not be selected, because no information supporting enzymatically assisted catalysis could be retained in subsequent development. If this line of reasoning holds, ribose would have been selected from the multitude of sugars purely for steric reasons, that is, because it is structurally best suited to form an anticodon in combination with bases and phosphate.

It is striking that all tRNAs that are specifically charged with an amino acid today always possess the same base sequence CCA at the acceptor stem (Fig. 7). This binding sequence must have proven so successful in the earliest phase that it has been used exclusively up to the present day. The synthetases—today’s complex enzymes that carry out the specific charging of the corresponding tRNAs—recognize the now more complex tRNAs via their additional loops and the specific bases contained therein, thereby ensuring the critically important accurate assignment of the amino acid to be linked. The question remains why the version with the CCA acceptor arm emerged as the apparently sole representative from the group of medium-length RNAs through the selection process.

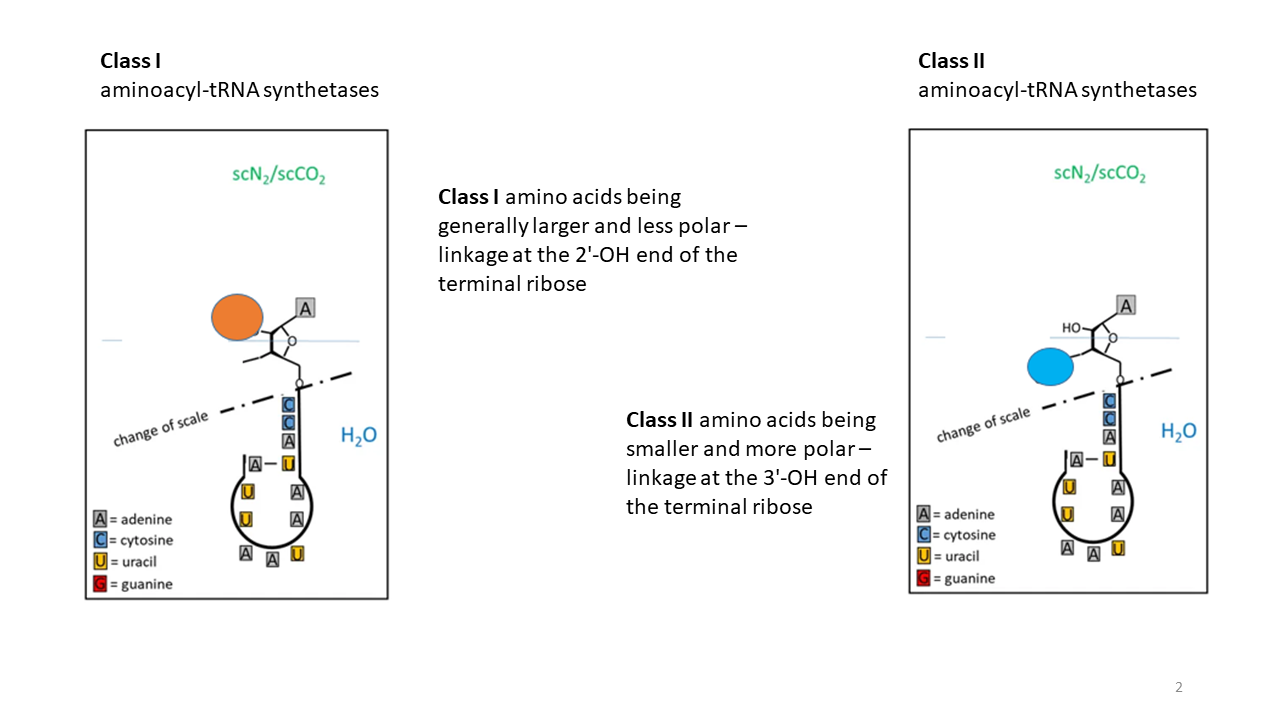

The cause may lie in an advantage conferred by a specific property of the proto-tRNA. In principle, any amino acid could have been attached to any proto-tRNA. Where, then, did the possibility for a specific assignment arise that is necessary for the establishment of an information storage system? Present-day conditions at least allow a coarse distinction. There are two classes of synthetases that perform the specific charging of tRNAs.

Class I synthetases catalyze the attachment of hydrophobic amino acids at the 2′-OH group of the terminal ribose (Fig. 8), whereas

class II synthetases

catalyze the attachment of hydrophilic amino acids at the 3′-OH group [13].

Fig. 8 Hydrophobic amino acids are linked to the 2′-OH of the ribose by class I tRNA synthetases, whereas hydrophilic amino acids are linked to the 3′-OH by class II tRNA synthetases. The blue line, representing an interface between a hydrophobic (upper) and a hydrophilic environment (region shown not to scale), would constitute a possible separation boundary for the two linkage sites during the early phase of development.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

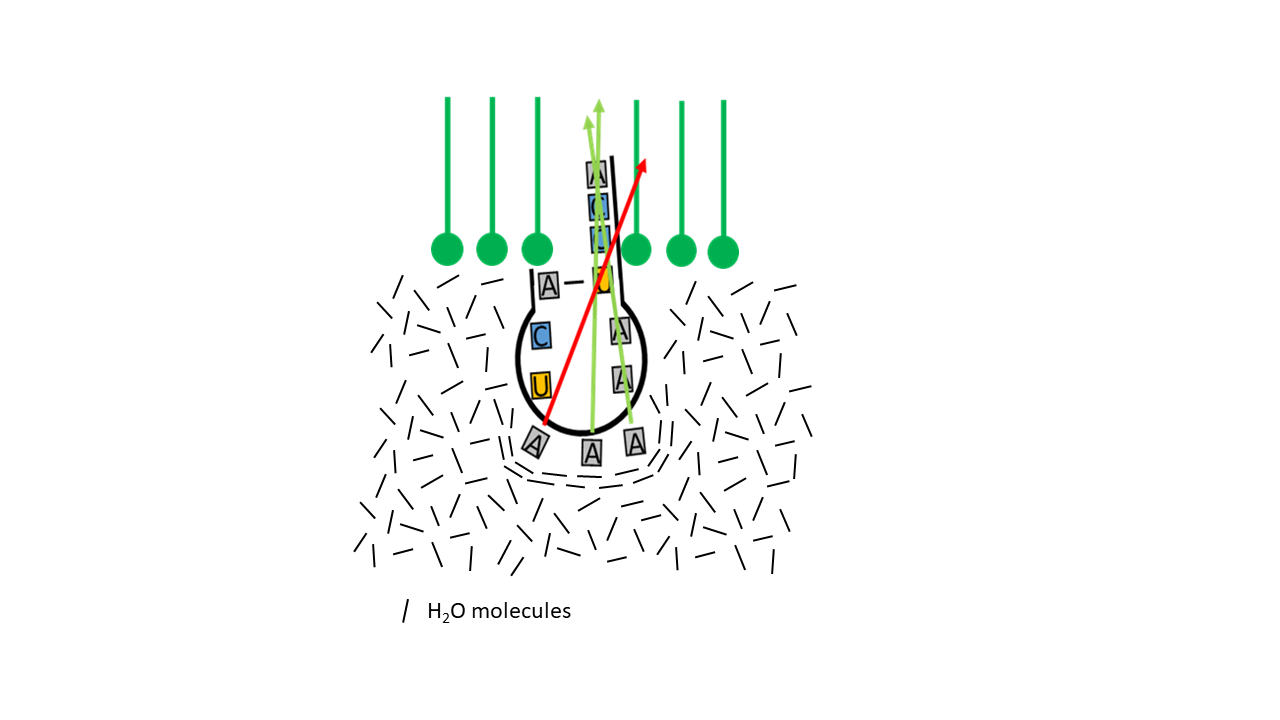

However, it is necessary to first identify the enrichment potential of a specific type of RNA that possessed the characteristics of a proto-tRNA. It is possible that flotation processes, aided by collector molecules and ascending supercritical gas bubbles, transported suitable RNA molecules to the precipitation zone. Lipids (amphiphiles) are capable of this process, consisting of a hydrophilic head and a hydrophobic tail (see Fig. 8 and 9). The head can bind to an RNA molecule (in the case of a proto-tRNA, with the CCA end or other attachment sites) (see also [14]). While the hydrophobic portion can be encapsulated in a supercritical gas bubble, the hydrophilic remainder remains with the RNA in the water. The gas bubbles rise and transport the molecules to gas pockets, where they accumulate. From there or directly, they reach the boundary zone where the supercritical state transitions to the subcritical state. While other RNA variants can be transported similarly, hydrophobic organic molecules transfer directly into the bubbles and ascend with them. At approximately 1000 meters depth, during a phase transition caused by pressure decrease during a geyser eruption, all transported molecules are enriched in the water and at the interface with the gas phase.

Fig. 9 Schematic illustration of a flotation process: amphiphilic lipids are linked to the acceptor arm of a proto-tRNA. The hydrophobic moiety is incorporated into bubbles of supercritical CO₂/N₂, while the hydrophilic head group, together with the RNA, remains in the aqueous phase. The bubbles rise and accumulate in the upper region of a cavity. Some of the molecules enter completely into the supercritical CO₂/N₂ (sc = supercritical) reservoir, whereas others position themselves precisely at the water surface. Only the postulated proto-tRNA as the key molecule is shown. Other RNA variants are linked and transported in an analogous manner. Hydrophobic organic molecules can pass directly into the bubbles and be transported upward as well.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

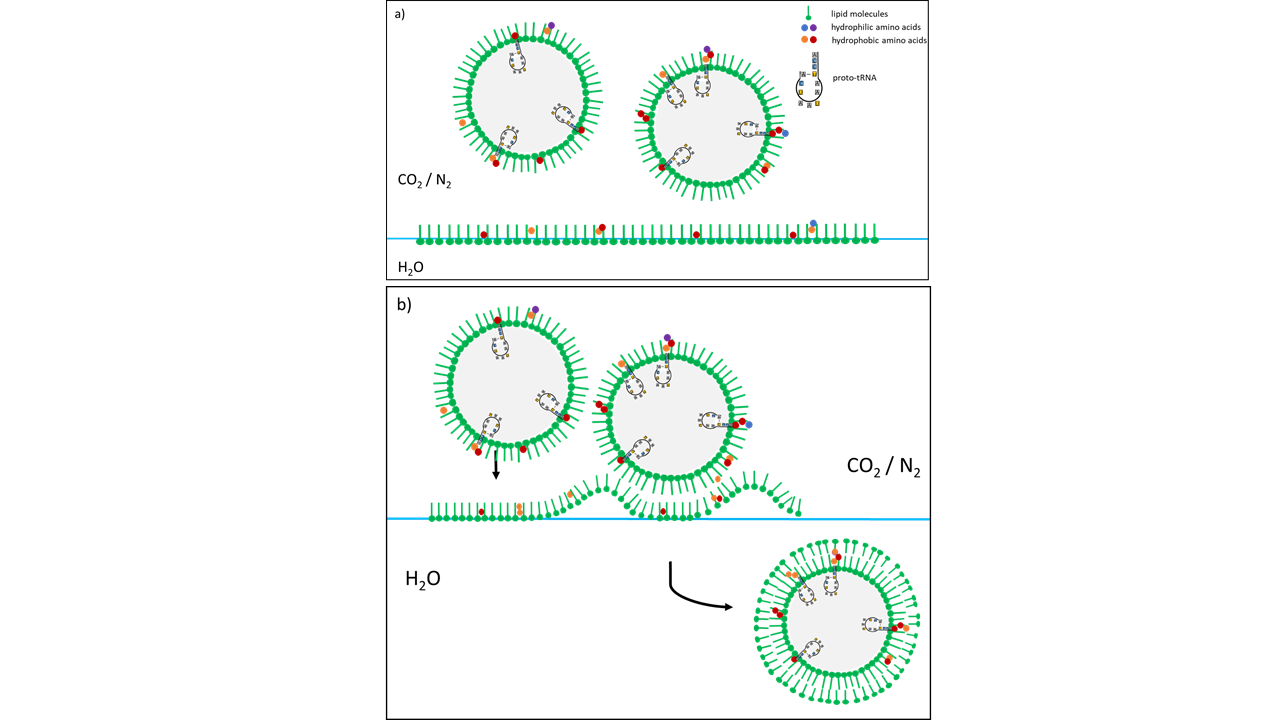

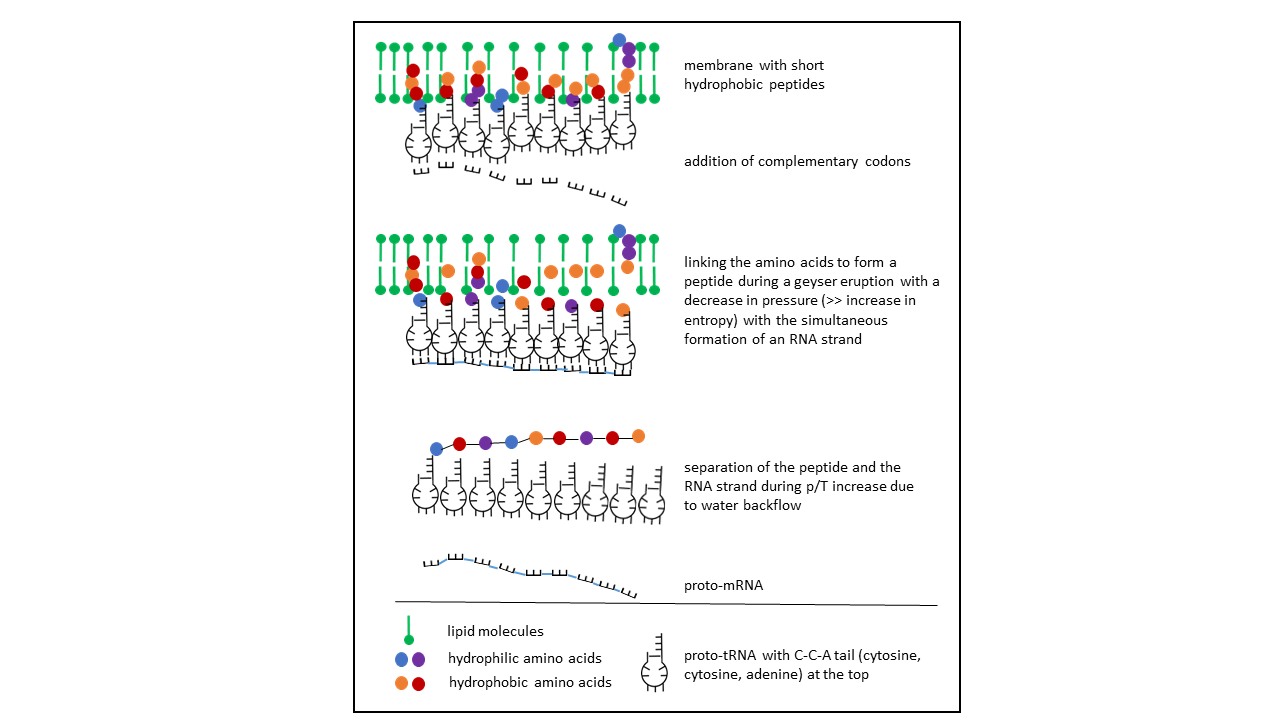

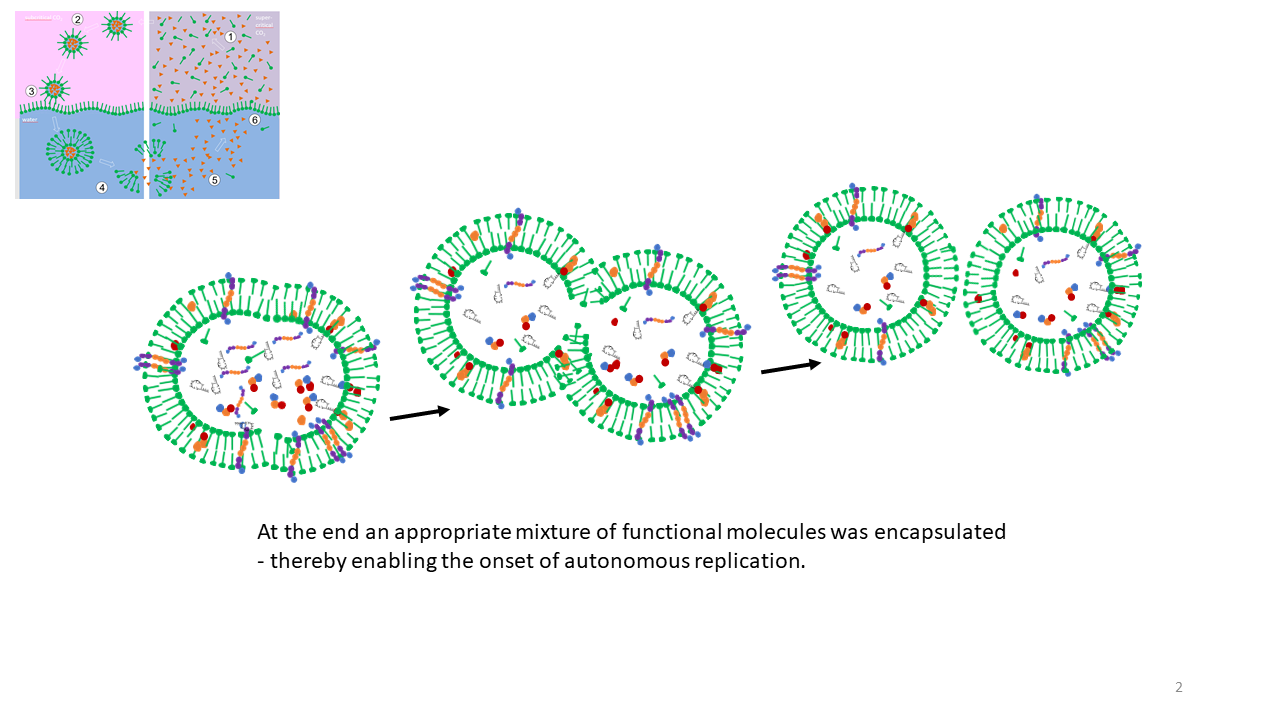

The vesicle formation

Mayer et al. [2, 12] were able to demonstrate the formation of vesicles and chemical evolution of peptides in high-pressure experiments. The conditions of the upper crust were simulated with numerous cavities and a cold water geyser system. The focus of the experiments was on the depth of about 1000 m, the transition area from scCO2 to gas. A large number of cavities, in which the CO2 accumulates, appear along the tear-off edges on the fault surfaces. This creates reaction chambers with two phases, water in the lower part and scCO2 or gCO2 in the upper part. If scCO2 is present, the pressure drop during a geyser eruption in the border region leads to a phase change. CO2 gas is produced in which dissolved water condenses to form a mist (corresponds to salt-free condensed water).

V1 Video showing the interior of the high-pressure cell depicted in Figure 1: The lower half contains water, which is being stirred by a magnetic stirrer. The upper half contains supercritical scCO2 (scCO2) and gaseous CO2 (gCO2).

The pressure, initially above the threshold for supercritical CO2, is gradually reduced. As the pressure drops below the supercritical state, mist droplets form from the small amount of water dissolved in the scCO2. These droplets acquire an initial lipid coating within the gas phase. Upon descending to the water surface, which is also coated with lipids, a second lipid layer forms around the droplets. The result is vesicles composed of condensed water droplets enclosed by a lipid membrane.

As the experiments have shown, this is the starting point for vesicle formation, since lipids from the scCO2, which cannot remain in the gas, collect to form a first shell on the outer surface of the droplets. The sinking to the water interface, which is also covered with lipids, leads to a further encapsulation, so that vesicles with a double membrane are then present in the water. Added amino acids linked to form peptides during depressurization and interacted with the membrane of the formed vesicles.

V2 MD simulation as an example of the behavior of hydrophobic peptides (here 8 amino acids) in a membrane. The blue dotted areas are water molecules. The membrane consists of lipids with gray, hydrophilic heads and green, hydrophobic tails that point inwards. Clip courtesy of Maria Davila Garvin and Christian Mayer, Physical Chemistry at the University of Duisburg-Essen. Questions and suggestions should be directed to them directly: maria.davila@uni-due.de christian.mayer@uni-due.de

With a renewed increase in pressure due to back-flowing water after the end of the eruption, most of the vesicles are destroyed again. In the end, Mayer et al. show that chemical evolution is possible through cyclic repetition of the pressure fluctuations, which leads to the mutual stabilization of peptides and vesicles.

Fig. 10 Vesicle formation following pressure reduction as a consequence of a cold-water geyser eruption. (a) Mist droplets are coated with a lipid envelope. (b) Upon contact with lipids at the water surface, a second envelope is formed (based on Mayer et al. 2015 [2]). The vesicles consist of distilled water containing a fraction of organic molecules. The difference in salt concentrations between the exterior (high) and the interior (salt-free) leads to instability, resulting in rapid destruction during the next geyser eruption. The same vesicle-formation process occurs with water splashes that are thrown above the water surface during a turbulent geyser eruption. The vesicles formed in this manner are considerably larger, contain much higher concentrations of organic molecules, and exhibit the same salt concentrations as the surrounding water. As a result, they are more stable than vesicles formed from mist droplets and provide higher concentrations of organic molecules for reactions. Amino acids (colored dots) and a specific RNA (see above) interacting with the membrane are depicted.

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

However, given the seemingly infinite number of possible combinations in peptide formation, no repetition of the same sequences in the amino acid chains can be expected. What is missing is a storage of the information about the sequence, as it can be found in the later formed RNA or DNA.

However, the importance of vesicle formation is reflected in several properties that have played an important role in the development of life.

- On the one hand, it becomes clear how easily vesicles can be formed as precursors of cell compartments.

- On the other hand, an interaction between the membrane and molecules occurs, which can lead to special reactions and chemical evolution.

- Furthermore, the type of vesicle formation is suitable for taking up large molecular complexes that are formed in the free environment of the cavities during droplet formation.

The results obtained so far give rise to far-reaching considerations for new research questions and experimental designs. For example, in addition to the canonical L-amino acids previously used, D-amino acids can be employed as alternatives in the same experimental series. It is of particular interest to investigate whether chemical selection in peptides containing D-amino acids leads to the same sequences as those observed in peptides with L-amino acids. Another experimental series could be conducted using racemic mixtures, where the proportions of both isomers are equal.

Of particular interest are the sequences of D-peptides for pharmaceutical research, especially in the context of developing new antibiotics. For this purpose, additional components must be integrated into the vesicle formation process to enable specific selective steps.

A possible experimental design involving D-amino acids and L-ribose in RNA could serve as a starting point for the development of a mirror-image cell.

Confronting risks of mirror life (DOI: 10.1126/science.ads9158)

The Hypothetical Model for Information Storage

For the storage of information on amino acid sequences in peptides, a mediating molecule must have been required that corresponded to a simple version of a tRNA (see above). This proto-tRNA is assumed in the model presented here for the development of the first cell. The use of DNA as the carrier of genetic information is assumed to have occurred at a later stage, since its stability under the conditions of hydrothermal disturbance zones would not have been sufficient.

The Onset of Information Storage

The formation of vesicles under pressure and temperature conditions corresponding to depths of approximately 1,000 m within the continental crust of the young Earth (see above) has been demonstrated repeatedly in laboratory experiments [2, 4]. Up to twelve amino acids can be formed under hydrothermal conditions in the crust [15, 16], with their relative abundances depending on the specific formation conditions. The hydrophobic amino acids isoleucine, valine, leucine, and phenylalanine—known to be formable under hydrothermal conditions—could theoretically be incorporated into membranes during vesicle formation, although energetic barriers exist. This limitation does not apply when several identical or similar amino acids associate to form short peptides; in this form, incorporation into the membrane becomes readily possible. The hydrophilic amino acids threonine, serine, proline, glutamic acid, aspartic acid, and lysine remain in the aqueous phase of the droplets unless they are incorporated into peptides predominantly composed of hydrophobic amino acids. Glycine, as the only non-chiral amino acid, represents a special case and can occupy different positions.

The vesicles consist of distilled water containing a fraction of organic molecules. Differences in salt concentration between the interior and exterior lead to instability, resulting in rapid destruction during the subsequent geyser eruption. The same vesicle-formation process occurs with water droplets that are hurled from depth above the water surface of the cavity during a turbulent geyser eruption. The vesicles formed in this manner are significantly larger, contain much higher concentrations of organic molecules, and exhibit the same salt concentrations as the surrounding water. As a result, they are more stable than vesicles derived from mist droplets and provide higher concentrations of organic molecules for chemical reactions.

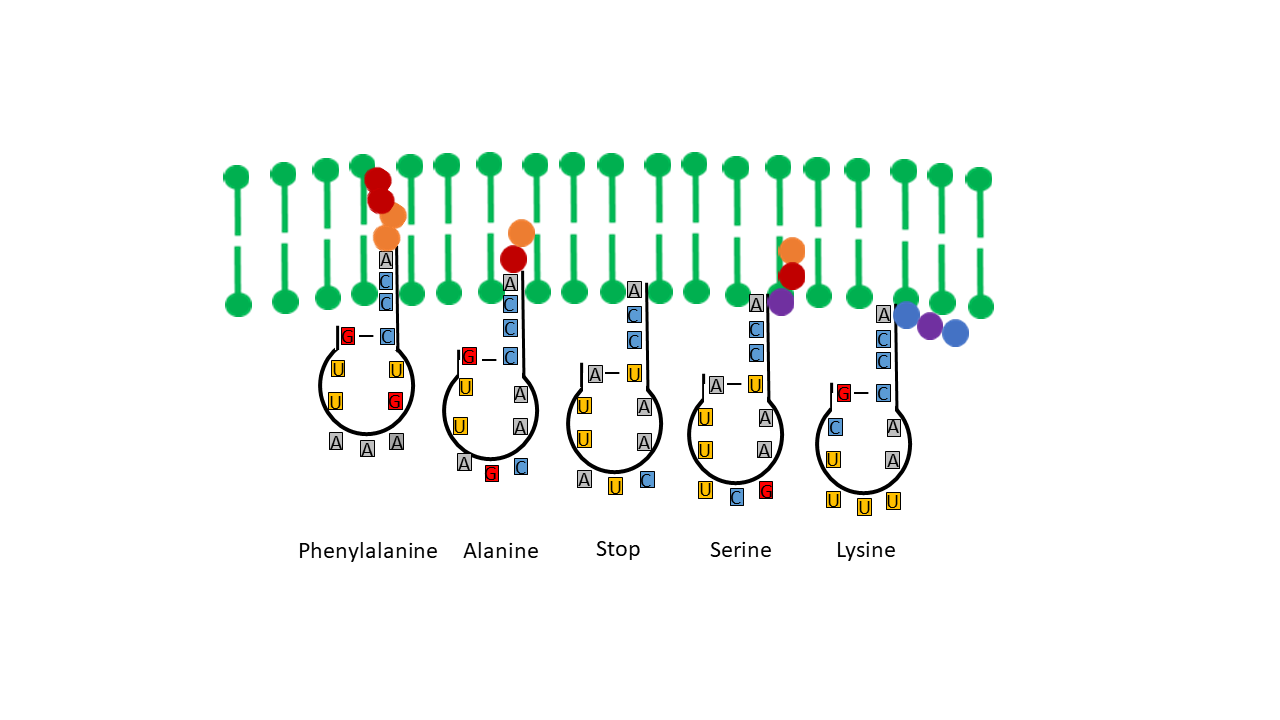

Hydrophobicity as a controlling factor

In the simple proto-tRNA outlined above (Fig. 7), the adenine base is positioned precisely at the tip of the strand that is unpaired in this model, owing to the base sequence ACC. The acceptor arm can penetrate the membrane due to the hydrophobicity of adenine, thereby coming into contact with hydrophobic amino acids (Fig. 11). Under these conditions, linkage at the 2′-OH position of the terminal ribose becomes possible within the geyser cycle.

Fig. 11 Variation in Penetration Depths of the Acceptor Arm into the Membrane Depending on the Hydrophobicity of the Anticodon

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The question arises as to how a specific association of a given amino acid with respect to the anticodon base triplet could have been achieved. At the base triplet that ultimately defines the code, three of the four possible bases are always present, differing in their hydrophobicity [10]. Depending on the nature of the participating bases and their positions within the triplet, different values arise for the entropic force associated with the hydrophobic effect, contributing to different depths of penetration of the acceptor arm into the membrane (https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hydrophobie).

This implies that the greater the hydrophobicity in the anticodon region, the further the tip of the proto-tRNA protrudes into the membrane. Upon contact with a terminal amino acid of a peptide, the amino acid can be transferred and bound to the tip of the proto-tRNA while being cleaved from the peptide chain. Detachment of the amino acid from the chain increases entropy and thus favors the reaction. The linkage binds the amino acid at the 2′-OH position. With appropriate combinations of bases in the anticodon, different, finely tuned positions of the CCA arm within the membrane are achieved, enabling linkage to amino acids of differing hydrophobicity that occupy different positions within the membrane (during pressure decrease accompanied by gas phase transitions). On average, the residence probability of the most strongly hydrophobic amino acids is greatest in the innermost zone. If more hydrophilic bases are present in the anticodon, the CCA arm does not extend as far into the membrane, such that hydrophilic amino acids are linked at the 3′-OH position. In an intermediate position, no amino acids can be attached. The corresponding combination is equivalent to the modern stop positions encountered during mRNA decoding in the ribosome.

Backing

[The model initially appeared speculative, as there was no evidence beyond the presumed entropic effect that an RNA molecule—even one containing only a short single-stranded segment—could penetrate a vesicle membrane. The prevailing view held that RNA could at most align parallel to the membrane surface. In mid-2025, Czerniak and Saenz published a review summarizing and evaluating previous work on RNA–lipid interactions [26]. The authors note that, despite the strongly hydrophilic nature of nucleic acids, nucleobases have been observed in close proximity to the hydrophobic core region of lipid membranes, and that guanine, adenine, and uracil can interact with lipid chains. Based on the cited observations, they conclude that unfolded single-stranded RNA exposes nucleobases capable of interacting with deeper regions of phospholipid membranes [see Michanek et al. (2012); 27]. Such a mechanism is not possible for double-stranded species, in which the nucleobases are embedded within RNA helices. Notably, several experiments have identified RNAs that specifically bind to hydrophobic amino acids such as valine, tryptophan, phenylalanine, and isoleucine. This confirms, in their conclusion, that it is fundamentally possible for RNA species to bind to hydrophobic lipid chains.]

The ACC arm

From a mechanical perspective, fixing a finger in a plastic medium is more favorable when the tip is thickened (comparable to inserting a lollipop into firm pudding). With the base combination “ACC” in the acceptor arm, adenine—with its two ring structures (purine scaffold)—is followed by two smaller bases, cytosine, each with a single ring structure (pyrimidine scaffold). This combination likely proved to be the most favorable (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12 Fixation of the ACC arm within the membrane (lollipop-like structure for optimal embedding; catalytic function of the membrane).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

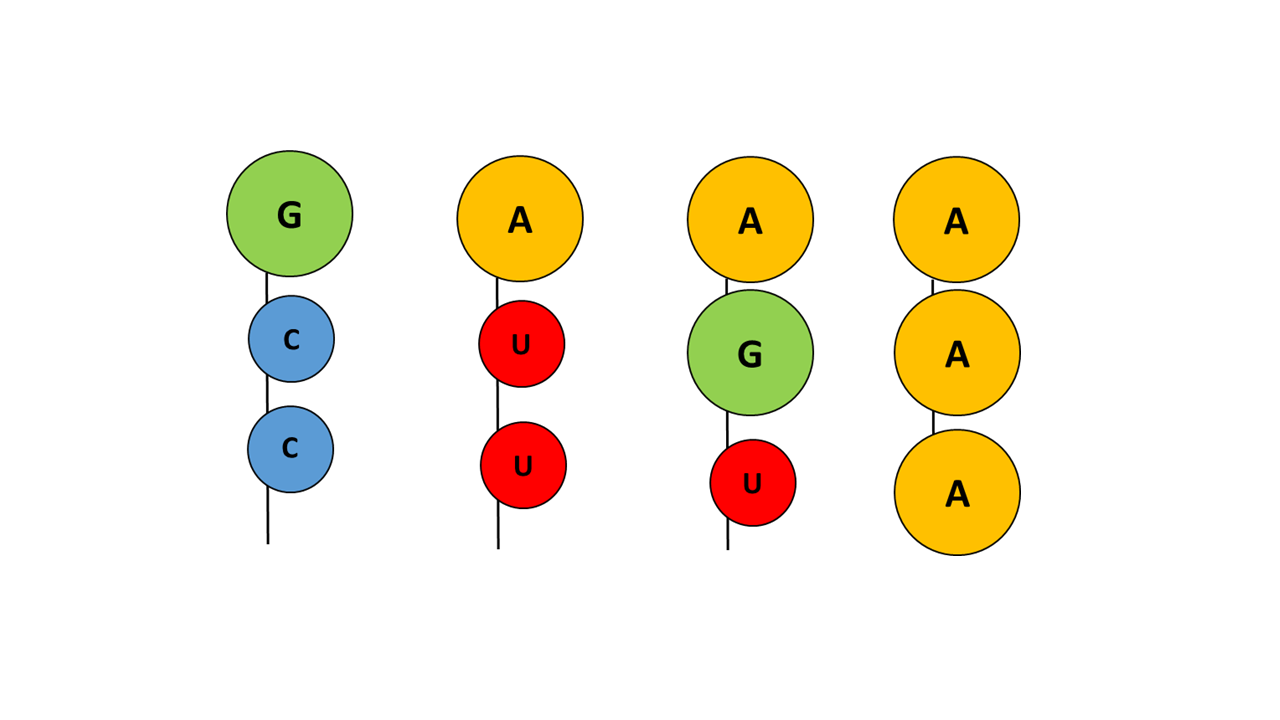

In the chemical evolution leading to the “ACC” arm, numerous variants must have arisen that were unsuitable or less suitable due to molecular size and/or degree of hydrophobicity (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13 Examples of variations of different base combinations of the acceptor arm that did not prevail

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

With guanine at the tip, a hydrophilic base is present that blocks penetration into the membrane, irrespective of which nucleobases follow. With adenine at the tip and the smaller pyrimidine base uracil, penetration of the acceptor arm into the membrane is possible; however, uracil is more hydrophilic than cytosine, making the combination with cytosine more favorable. If adenine is present not only at the tip but also at additional positions, fixation within the membrane becomes too strong, such that fine control of the penetration depth by the anticodon is no longer possible.

Wobble pairing

A particular feature relevant to the specificity of the genetic code is the variability of the third base of the mRNA codon (5′→3′) or, correspondingly, of the anticodon (3′→5′). In triplets encoding the same amino acid, there is often only variation in the third base (wobble pairing). Consequently, the contribution of the third base to specificity is lower than that of the first and second bases. It is worth considering whether a connection to the hydrophobic/entropic effect may have existed. For example, if the forces acting on a membrane-coupled proto-tRNA are considered in terms of force vectors (Fig. 14), the influence of the first two bases on the direction of penetration of the acceptor arm—due to molecular configuration—is greater than that of the third base.

Fig. 14 Direction of the force vectors of the hydrophobic/entropic effect as a function of molecular structure.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

A first idea – but unrealistic

With these relationships, a process can be derived in which dense occupancy of different proto-tRNAs along the inner surface of a vesicle membrane allows storage of an amino acid sequence in an RNA molecule (Fig. 15). The curvature of the membrane would permit closely adjacent positions of the anticodons, enabling complementary association of codons and thereby the formation of an RNA (proto-mRNA). A difficulty arises, however, from the chirality of both the amino acids and the ribose, for which no selection mechanism for a homochiral peptide is present. For longer chains, an unmanageably large number of combinations emerges, requiring extensive timescales for exploration. A more efficient process is achieved if, alternatively, the proto-tRNA is cleaved at its single double-stranded region. It then exists as a single strand and can assume the function of a proto-mRNA (see below).

Fig. 15 Insertion of the proto-tRNA into the vesicle membrane with the CCA acceptor arm at the tip, depending on the hydrophobicity specified by the anticodon. After linkage of amino acids to the proto-tRNAs (hydrophobic amino acids, shown in yellow and red, are bound to short peptides within the membrane), the amino acids detach from the short peptides and link to one another to form a longer peptide. The closely spaced anticodons constitute the information store for the peptide sequence and serve as a template for a proto-mRNA, which arises through association of complementary nucleotides and subsequently detaches.

This possibility was not considered further, as the number of variations becomes effectively infinite when both ribose chiralities occur simultaneously.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

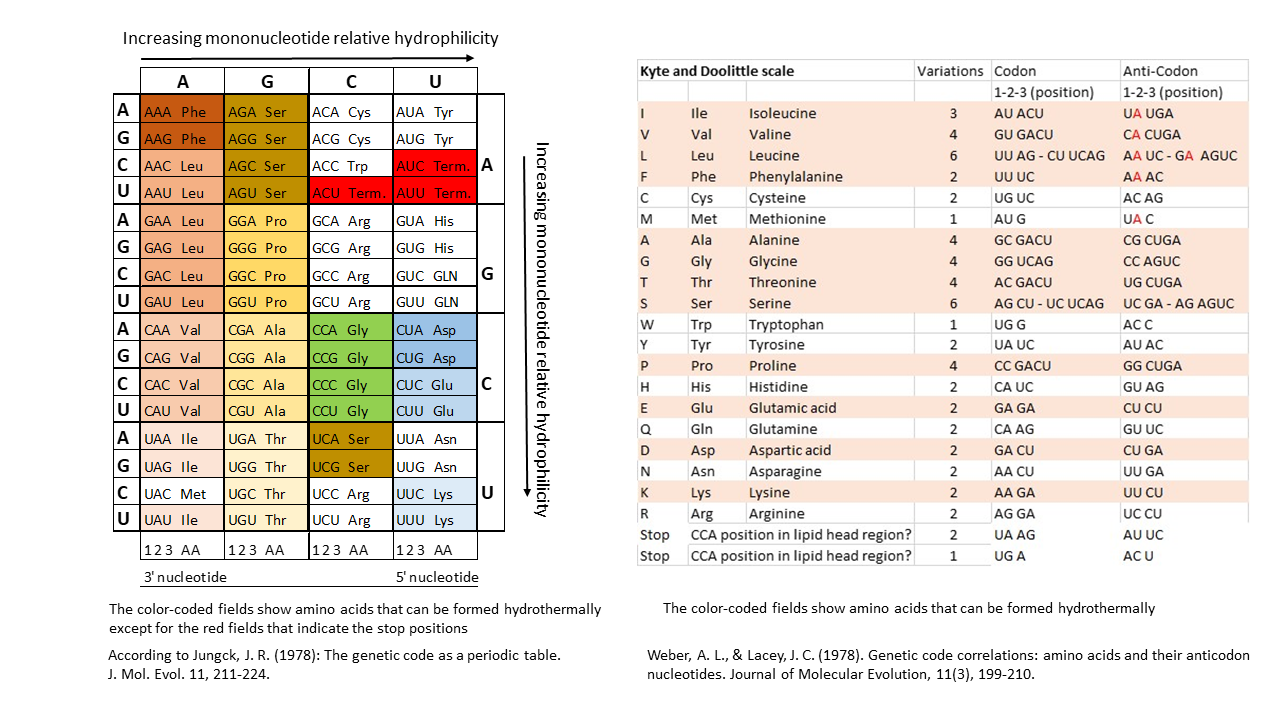

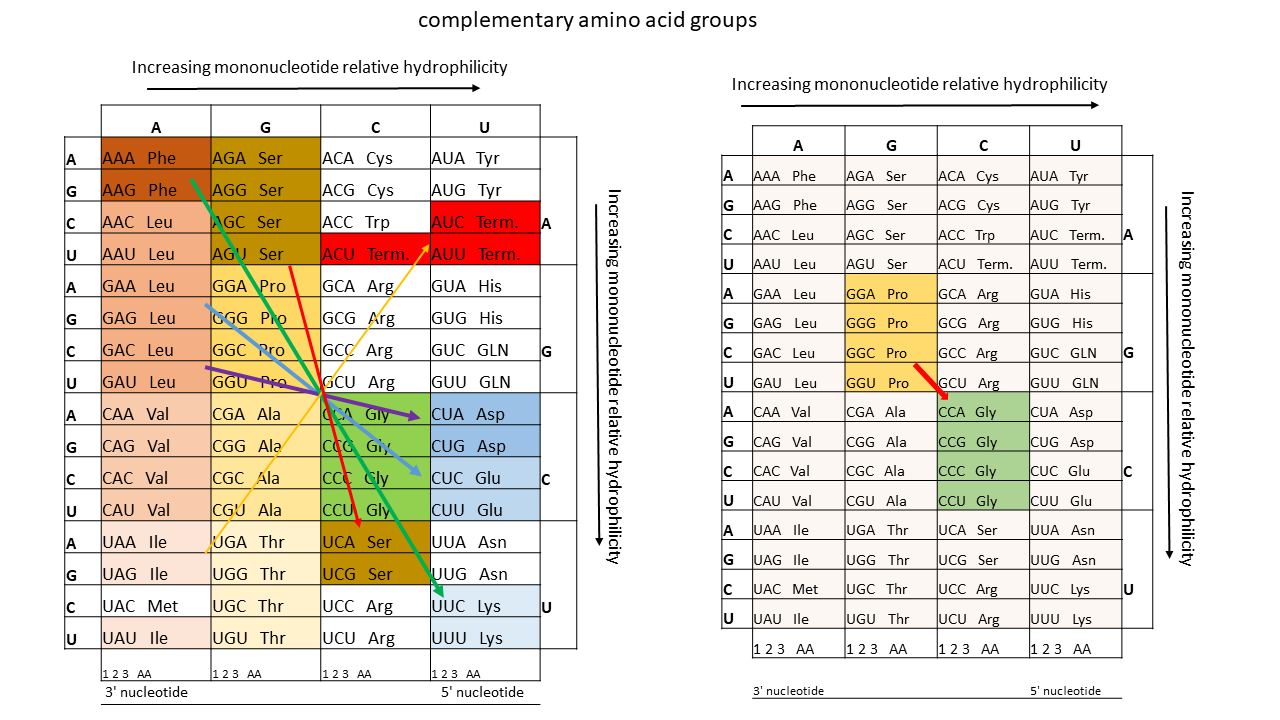

The proposed model of positioning the tip of a single-stranded proto-tRNA within a membrane requires a strict correlation between the hydrophobicities of the amino acids and those of the nucleobases or anticodons. Table 1 shows, when comparing anticodon assignments with their corresponding amino acids, that all hydrothermally formable hydrophobic amino acids possess an adenine in the central position and/or additional adenines at the periphery (right). Hydrophilic amino acids exhibit the opposite pattern. Weber and Lacey [17] already identified this striking correlation in 1978, although they were unable to provide an explanation. This relationship becomes particularly evident in the table compiled by Jungck (1978) when only hydrothermal amino acids are considered (colored fields, excluding codons at stop positions).

If the terminal ribose is at the level of the lipid heads on the inner edge of the membrane, there is no loading with an amino acid. The positions here correspond to the stop codons. In Table 1, when comparing the anti-codon assignments with the associated amino acids, it becomes clear that all hydrothermally formable hydrophobic amino acids have an adenine in the middle position or others in the edge area. The hydrophilic amino acids have a correspondingly opposite occupancy. Weber and Lacey [17] already discovered this striking correlation in 1978, without being able to offer an explanation for it.

Table 1 Left Side according to Jungck, J. R. (1978)[22]: This table provides a clear illustration of the relationships. Depicted are the relationships of three out of the four bases of each anti-codon to the encoded amino acid, depending on hydrophilicity (the first base on the left is the Wobble position). Amino acids that can be formed in hydrothermal systems are highlighted in color (exception: red for stop positions). Hydrophilic amino acids (shades of blue) are located in the corner with the most hydrophilic anti-codons. In contrast, Table 1 (right side) is presented for comparison. A sufficient explanation for these clear correlations has not been provided to date.

Table 1 Right Side: Canonical amino acids with decreasing hydrophobicity according to Kyte and Doolittle [20]. Hydrothermally formable amino acids are color-highlighted. For hydrophobic (hydrothermal) amino acids, the second position of the anti-codon on the tRNA (lower end) is occupied by the hydrophobic adenine (in red). In contrast, the tRNAs of hydrophilic amino acids possess the hydrophilic bases G, U, or C in this position.

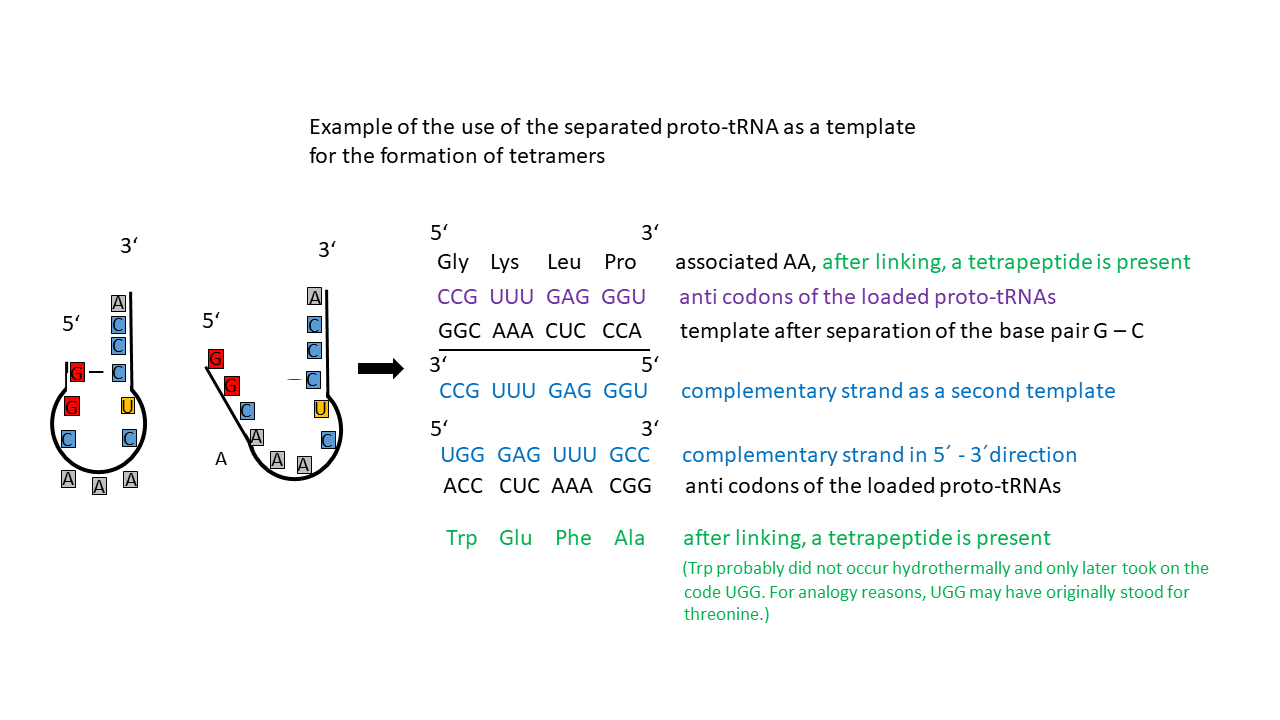

The different proto-tRNAs could thus be linked to amino acids in a relatively specific manner via the hydrophobicity of the anticodon. At the same time, the single double-stranded region of the tRNAs could be readily separated, yielding a single strand. In this context, adenine–uracil (A–U) base pairing is less stable than guanine–cytosine (G–C) pairing, which involves one additional hydrogen bond. The resulting single strand constituted an information strand that initially had no functional meaning due to its random nucleotide sequence. Because charged tRNAs were present simultaneously, and those stabilized by G–C base pairing remained intact longer upon temperature increase than proto-tRNAs with A–U pairing, they could use the “A–U” strand as a proto-mRNA and form a tetrapeptide, provided suitable conditions were present.

Some of the “tRNA templates” could not be used to produce a peptide because they provided positions for amino acids that did not yet exist. This also applies to the complementary strands generated during replication, which is regarded as a prerequisite for the survival of proto-tRNAs (Fig. 16). After replication, for example, the CCA segment in the complementary strand corresponds to the amino acid tryptophan, which was presumably not formed hydrothermally and only later occupied the UGG codon. By analogy, UGG may originally have encoded threonine.

Because proto-tRNAs had to exist in homochiral form (both D and L versions) in order to be formed as such, and because there is a preferential linkage of L-amino acids to D-RNAs (and vice versa) [23], the resulting peptides were also homochiral (present in equal amounts of both chiralities). Since at most twelve different amino acids could have been present with different proto-tRNAs—some of which may have existed in multiple forms for a given amino acid—a large variety of templates for tetrapeptides was available. The linkage of two tetrapeptides of the same chirality yielded lengths comparable to membrane thickness. This already allowed the formation of pores required for concentration equilibration. Because the peptide sequences were already stored, only the combination of tetrapeptide chains or of the corresponding complementary RNA strands was required to obtain the first functional molecules with catalytic activity. If these contributed to faster formation of additional functional and other “useful” molecules, they would win the competition for resources and establish their chirality.

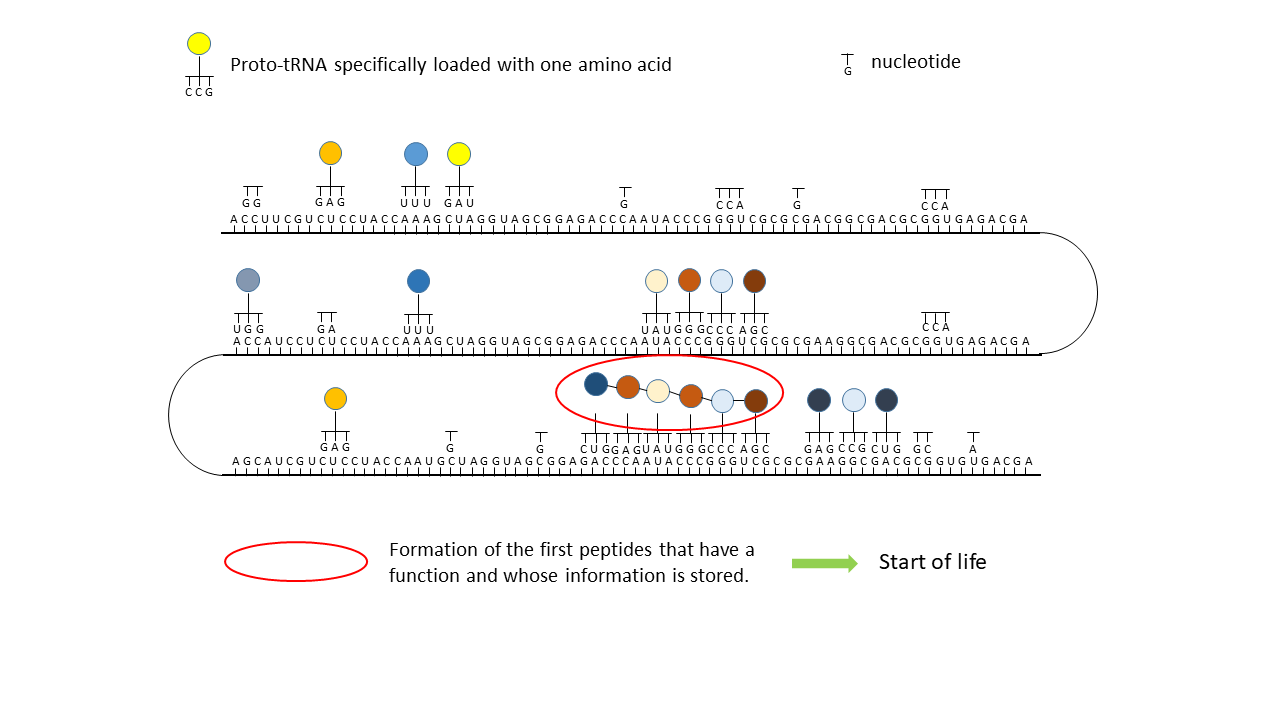

If this process for the first time involved a molecule with catalytic function that was subsequently retained, for example as the core of more complex peptides, this point may be regarded as the origin of life.

Advantage of using the opened proto-tRNA as a template:

If both the single strands of the tRNA (provided the codes correspond to hydrothermal amino acids) and, simultaneously, the complementary strands are used as templates (Fig. 16), catalytically active peptides can be generated that later, in DNA, exhibit bidirectional genetic encoding (sense/antisense orientation).

Fig. 16 Proto-tRNA as a single strand that can function as a template. An additional template is provided by the complementary strand. Tetramers can be formed from both, which are homochiral due to the tRNA. However, single-strand formation involving A–U base pairs was more readily achieved upon temperature increase, such that charged tRNAs with G–C pairing could already utilize these strands as templates.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

As mentioned above, there are two classes of synthetases responsible for the specific loading of tRNAs. Amino acids associated with Class I synthetases, which are linked to the 2'-OH end of the terminal ribose, are generally larger and less polar, while those associated with Class II synthetases, which are attached to the 3'-OH end, are smaller and more polar. Biochemical, bioinformatic, and protein engineering experiments support the hypothesis that these two classes originate from opposite strands of the same ancestral gene [25]. This would support the idea that the basis for the evolution of today's aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases dates back to a very early phase, which is related to the template formation described above.

Table 2: Complementary groups of amino acids that can exhibit a relationship in the use of templates from proto-tRNAs and their complementary strands.

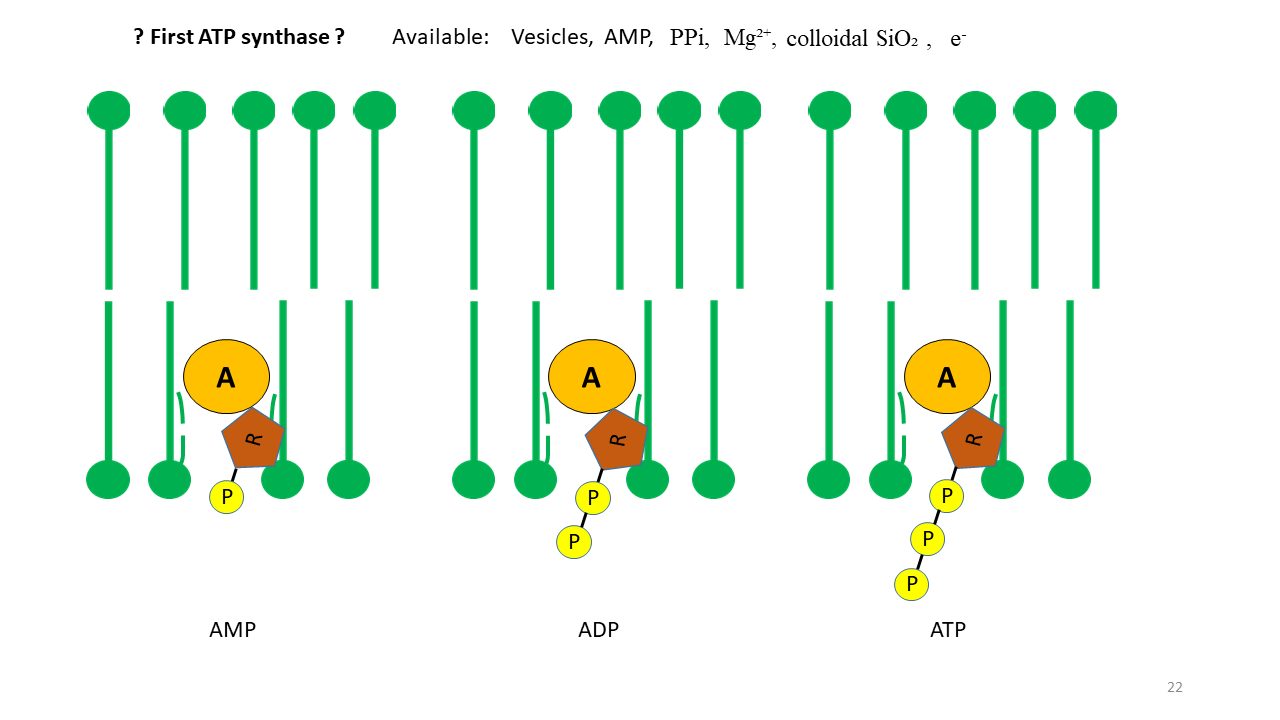

ATP

Of particular interest is the formation of ATP (adenosine triphosphate), which is the principal energy carrier in modern cells. ATP is produced by a complex process that evolved only gradually over evolutionary time. For many reactions at the onset of life, ATP would have been an attractive energy source. As shown above, the vesicle membrane can act as a catalyst. If proto-tRNA with adenine at its tip is able to penetrate the membrane, this must also have been possible for AMP (adenosine monophosphate) (Fig 17). Assuming that the required molecules were present, the formation of ATP can therefore be postulated. Corresponding experimental approaches appear conceivable.

Fig. 17 The membrane as a catalyst for positioning adenosine phosphates. Through fixation of AMP (adenosine monophosphate), the formation of ADP (adenosine diphosphate) and ATP (adenosine triphosphate) becomes conceivable. In addition to AMP, the presence of phosphate, Mg²⁺, colloidal SiO₂, and electrons generated by piezoelectricity was required, all of which were available.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Consequences

From the relationships discussed above, the following assumption can be made: both the single strands of the proto-tRNA consisting of twelve nucleobases and, simultaneously, their complementary strands could be used as templates from which catalytically active peptides were formed.

The four triplets of each possible proto-tRNA (there were more than 65,000 possible variations; the same number of tRNAs with opposite chirality is not discussed here) initially lacked the informational content required for a functional molecule. They represented random combinations from which tetramers could arise. A prerequisite, however, was that suitable tRNAs and corresponding amino acids were available for the respective triplets, since not all amino acids were present in this environment at the beginning. If such an RNA was copied repeatedly, the information about the sequence of the corresponding tetramers was also retained.

And chirality?

The development of chemical evolution toward D-ribose in RNA and L-amino acids in peptides might possibly be explained by a случайный (random) excess of one enantiomer at a particular point in time, although this is difficult to reconstruct. In principle, equal amounts of D- and L-molecules always exist, such that all reaction steps in the initial phase must have occurred with both. This would have remained the case until the point at which the first catalytically active peptide emerged that was stored in RNA and decisively shaped further development (the start of life). This peptide ensured that, through faster formation of successor molecules, resources were increasingly consumed by this group (today’s D-ribose and L-amino acids) [18, 19]. The probability that such a peptide arose at exactly the same time in both the D- and L-forms is vanishingly small.

A three-way relationship: membrane, peptide, and RNA — the MPR world

From the preceding considerations, it becomes clear that there was no isolated “RNA-first,” “peptide-first,” or “metabolism-first” world, as described above. Rather, three players must have coexisted simultaneously, undergoing chemical evolution in mutual interdependence: the vesicle membranes, which enabled separation of hydrophobic and hydrophilic amino acids; peptides, which initially formed unspecifically and later in an information-driven manner; and an RNA composed of the minimal possible number of nucleotides. In abbreviated form, this can be termed the MPR world.

Whereas some other models require information for enzyme formation to be present at the very beginning, the model presented here proposes that an unspecific sequence of codes arose first, which could be coupled to a sequence of amino acids in peptides. Only after a proto-enzyme crystallized out of random combinations from the pool of many unspecific codes—one that possessed properties supportive of further cellular development—was the information fixed as such in the RNA, which thereby became established as a proto-mRNA. Accordingly, it was passed on to subsequent generations by copying of the proto-mRNA. Only through validation by selection did the segment stored in RNA, and later in DNA, acquire its functional significance.

An interesting consideration arising from these ideas concerns the further evolution of enzyme formation, by which the rate of emergence of the first cells was determined.

What situation is conceivable? It is possible that a larger number of 12-nucleotide modules were linked to form a longer proto-mRNA strand (Fig. 18-1). Provided that specifically charged proto-tRNAs occupied appropriate positions and the transported amino acids could be linked into a chain, it was only a matter of time before certain combinations yielded catalytically active peptides (proto-enzymes).

It must be taken into account, however, that only parts of the proto-mRNA were occupied at any given time, since suitable tRNAs and amino acids did not yet exist for all triplets and/or sufficient building blocks were not available. Some of today’s canonical amino acids appeared only later in evolution.

One may envision the situation as analogous to a toothed belt strand from which many teeth are missing. Longer complete sections are bounded by gaps. For mRNA, the longer sections would correspond to regions from which a continuous amino acid chain could be formed. The delimiting gaps would thus have assumed the function of start and stop triplets that later became necessary for the decoding process.

And now it becomes particularly interesting: If, due to external influences or to enzymes that had meanwhile become active, a new amino acid with its corresponding tRNA (of which sufficient variants existed; see above) appeared in the system, the matching triplets of the mRNA that had previously remained unoccupied could suddenly be filled. This occurred not at a single site, but distributed across the entire strand wherever the corresponding codon was present. In the most favorable case, a gap between two peptide complexes was closed, and together they suddenly acquired higher functionality than either alone. This offered the opportunity to generate new large peptides/enzymes within a very short time, which represented more effective catalysts than the smaller precursor peptides on their own. In evolutionary terms, this could have resulted in major leaps forward each time. In contrast to a mutation that acts only locally, perhaps in a single individual, this change affected many positions within the information store and could thus occur simultaneously in all RNAs present in the environment.

This concept can also be applied to later stages of life’s evolution. Non-coding regions of DNA (so-called junk DNA) provide numerous points of departure for the establishment of new enzymes. Whenever major upheavals occurred in the Earth system, rapid adaptations of the biosphere to new environmental conditions followed. A particularly significant event in Earth’s history was, for example, the appearance of oxygen in the atmosphere. Oxygen can, for instance, convert the nucleobase guanine into 8-oxo-guanine, which can mispair with adenine instead of cytosine. It is unclear whether this specific effect occurred; it merely serves to illustrate that, through an environmentally driven influence affecting all or most organisms, even minimal changes in a single DNA component can rapidly lead to pronounced alterations in the blueprints of enzymes and other biomolecules.

Fig. 18-1

Fig. 18-2

Fig. 18-3

Fig. 18-4

Fig. 18-5

Fig. 18-6

Fig. 18-7

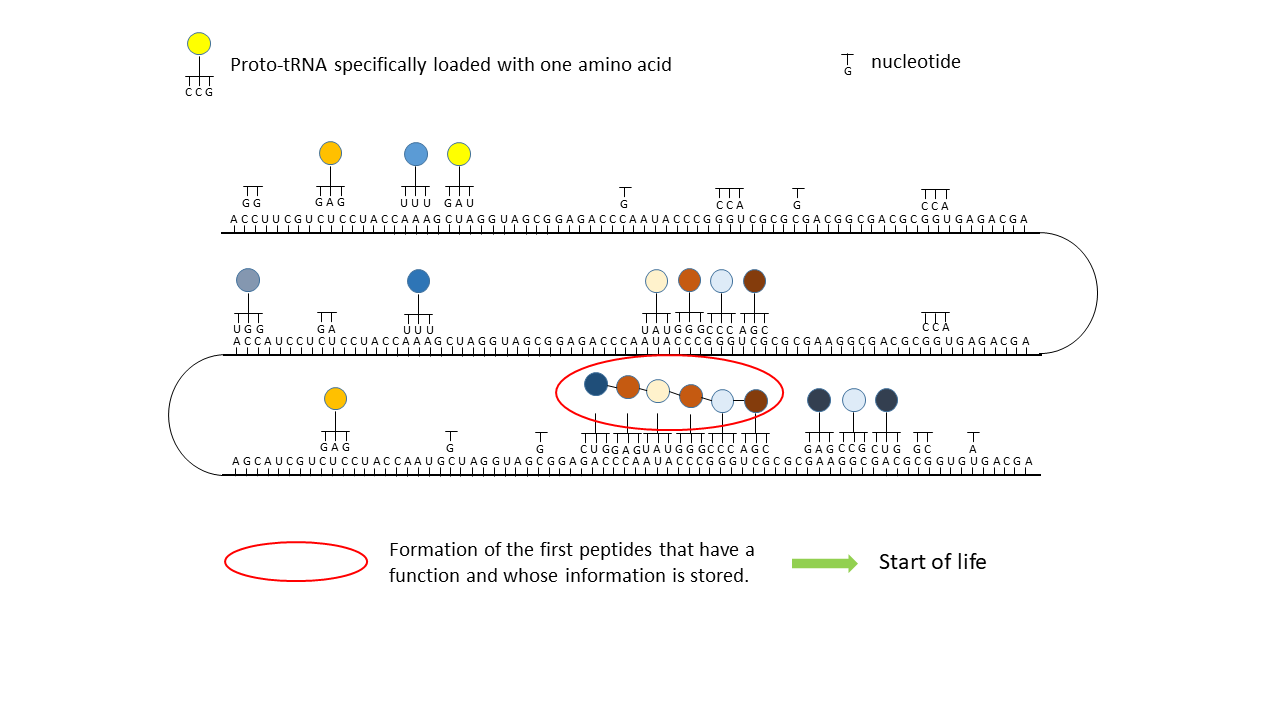

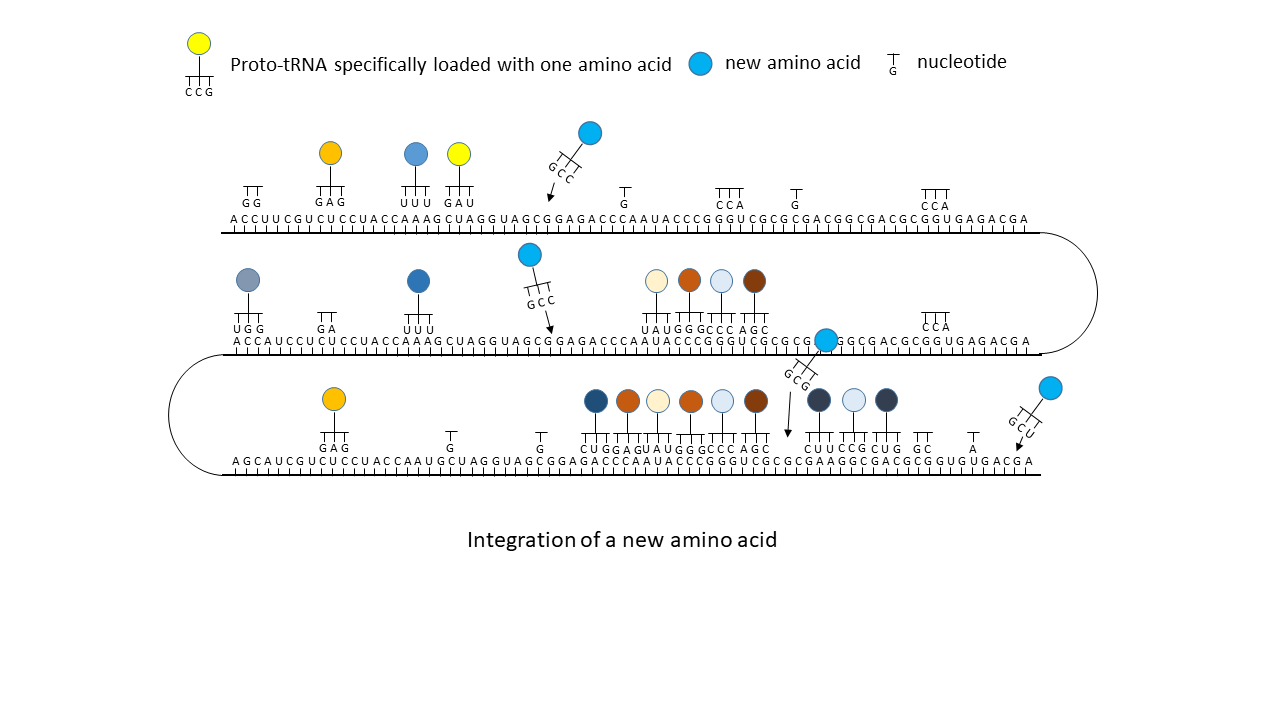

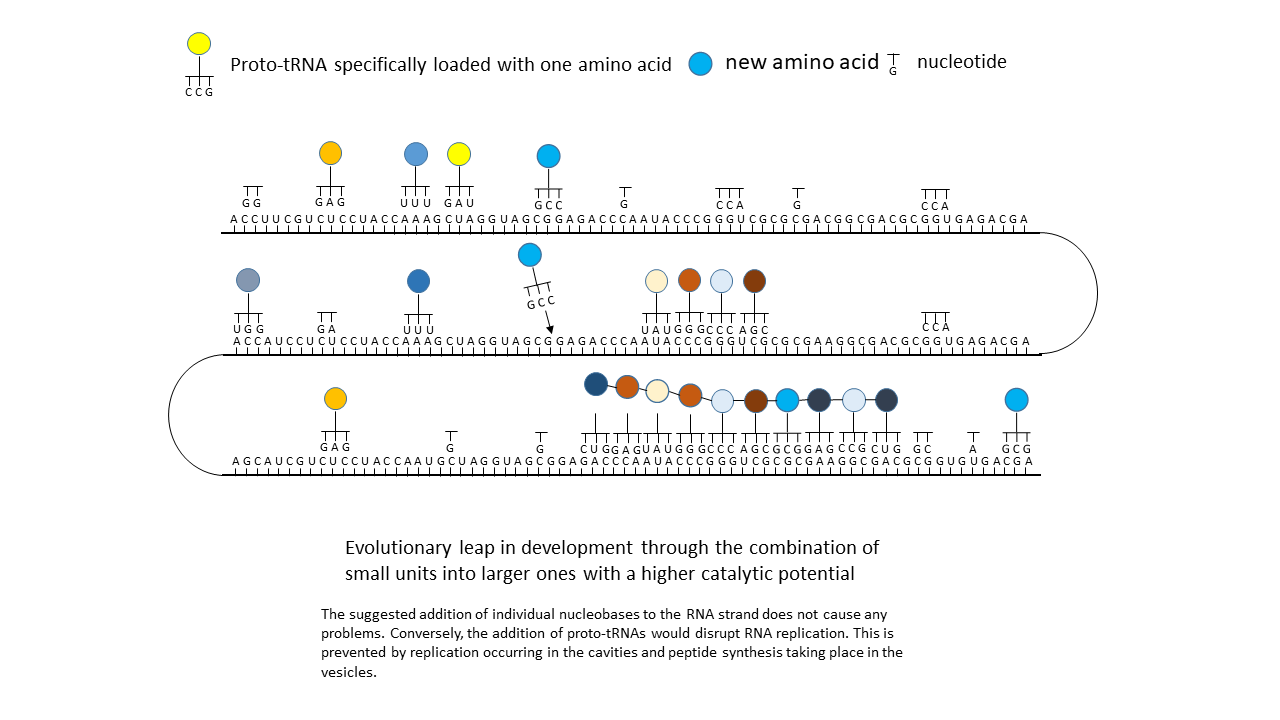

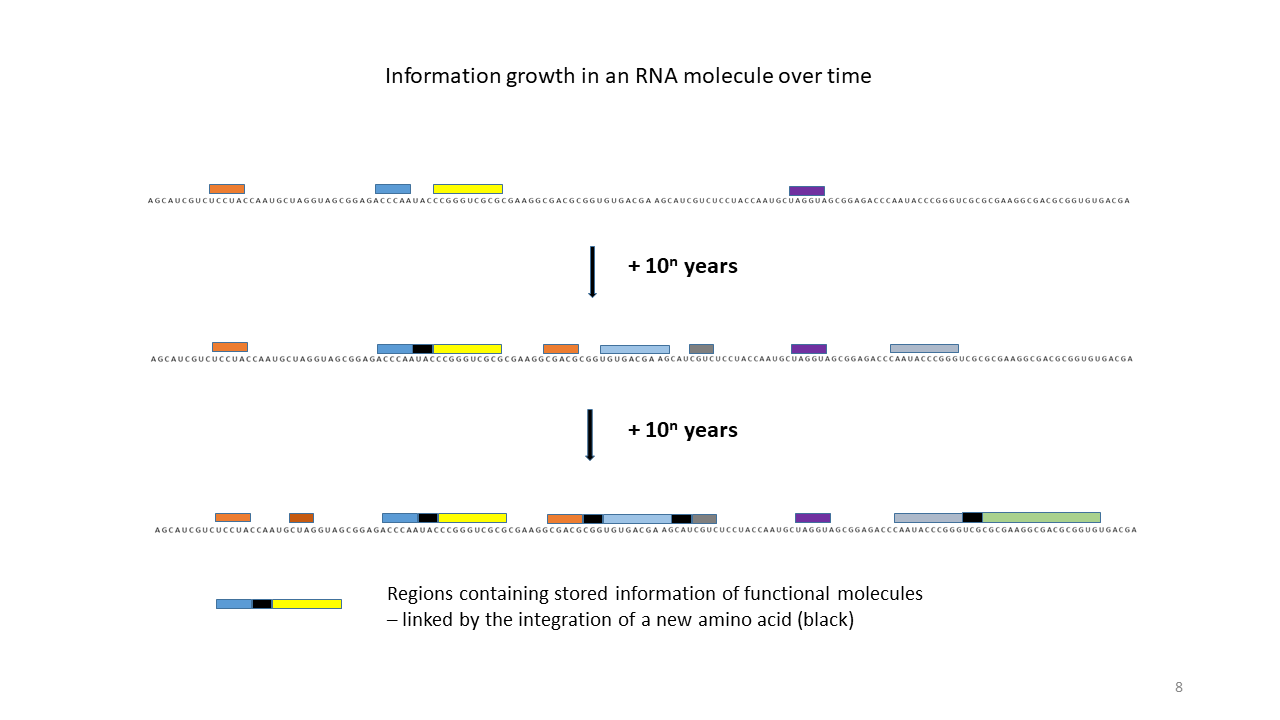

Fig. 18 1–7 Illustration of the occupation of a longer RNA “blank” by specifically charged proto-tRNAs. The amino acids (colored dots) were linked to the proto-tRNAs via the vesicle membranes.

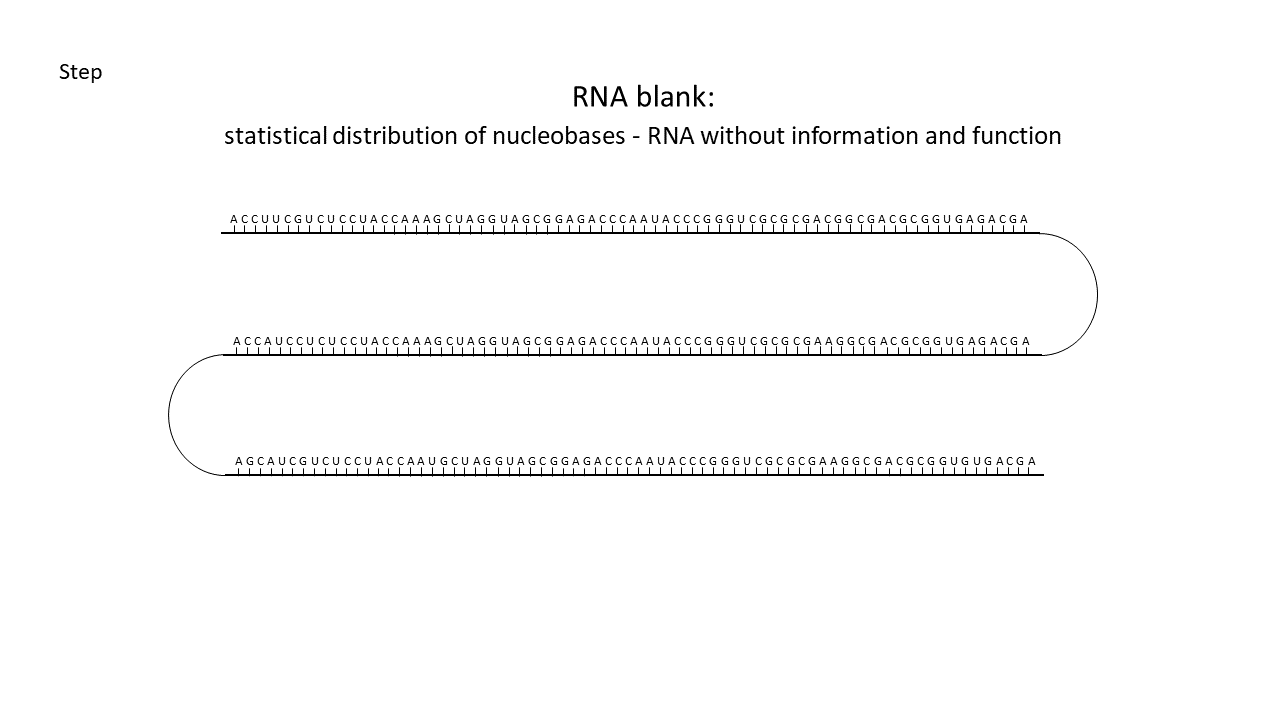

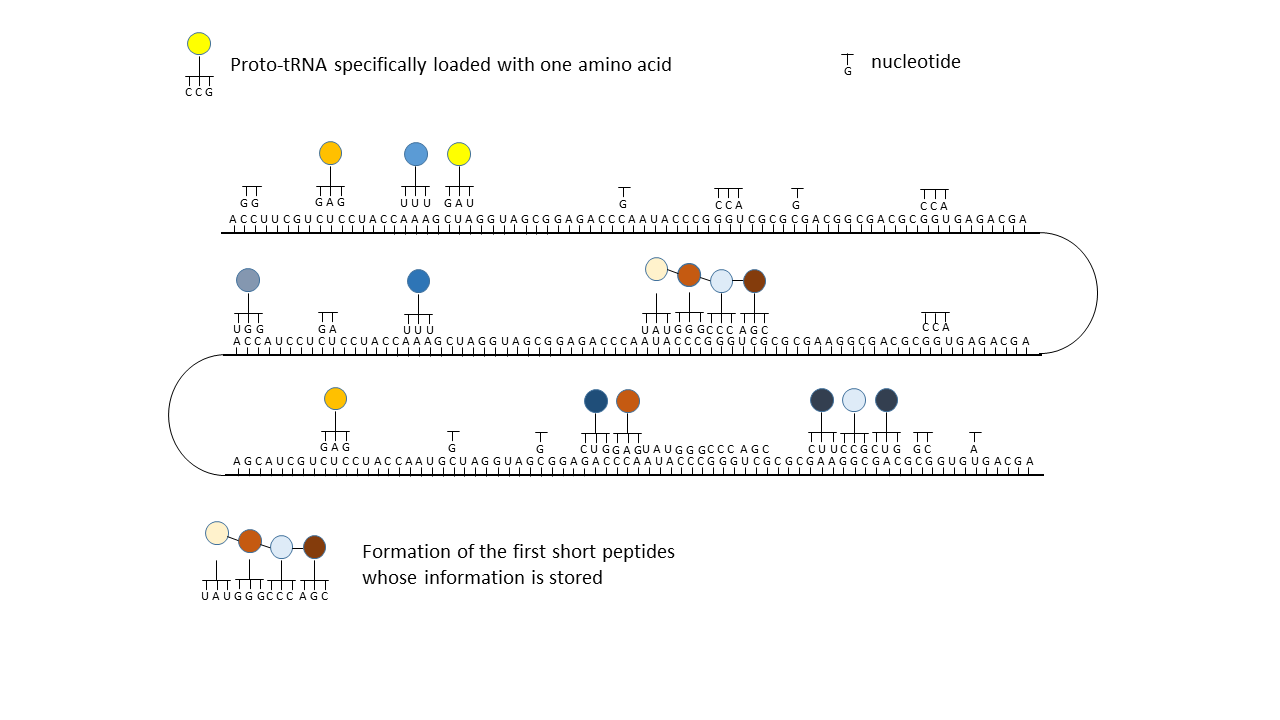

(1) RNA blank without informational content or function, which can be copied in the cavities.

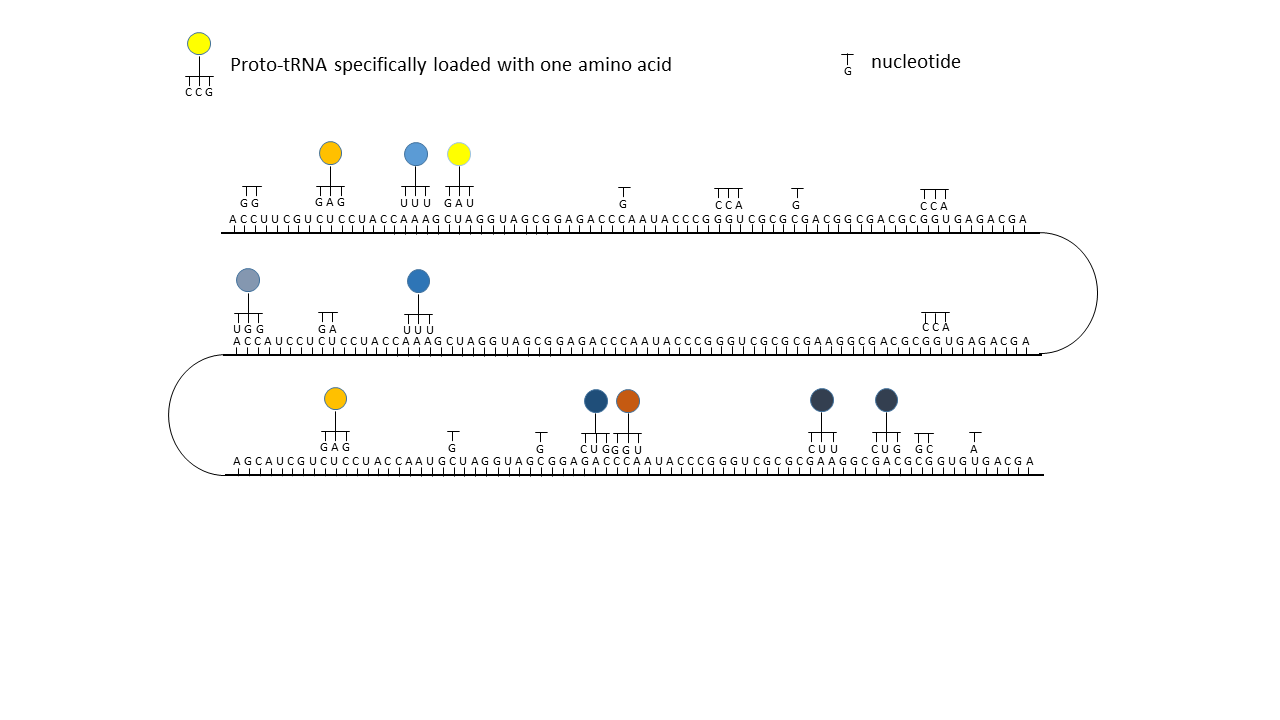

(2) RNA blank within a vesicle, where statistical occupation by complementary, specifically charged tRNAs occurs.

(3) Formation of initial peptides without function.

(4) Formation of the first peptides that, in the course of evolution, acquire function and whose sequences are stored; this point can be defined as the start of life. The postulated additional attachment of individual complementary nucleobases to the strand only partially impedes binding of proto-tRNAs. Conversely, proto-tRNAs would impede replication. This conflict is avoided if RNA replication takes place in the cavities and peptide synthesis in the vesicles.

(5) Integration of a new amino acid into the system.

(6) Closure of a gap between two storage segments of smaller enzymes by the new amino acid, yielding a new, longer enzyme with more effective catalytic activity: an evolutionary leap.

(7) Increase in functional segments along the RNA strand over time.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The Keystone

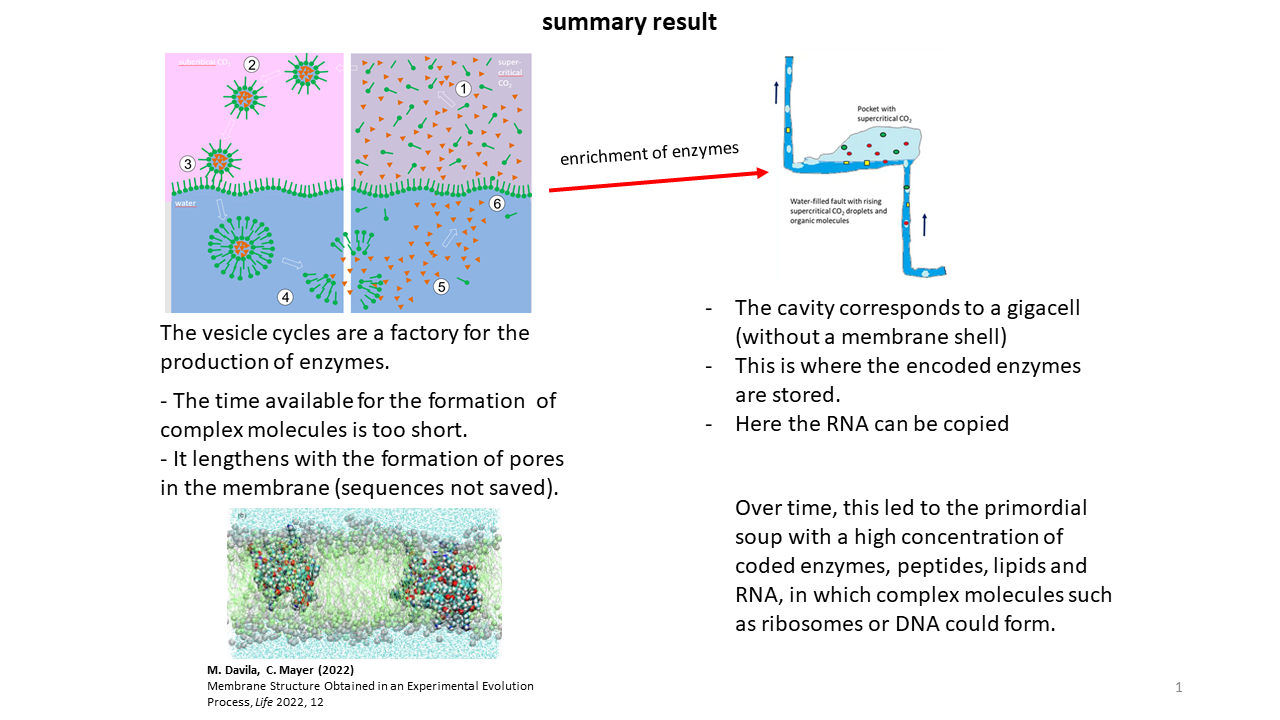

It has become clear that there was an interplay between vesicle formation and processes occurring within the cavities of continental fracture zones. Within these cavities, organic molecules initially accumulated, including building blocks required for the formation of the first cells. Through vesicle formation, these building blocks (amino acids, nucleobases, lipids, among others) were taken up, enabling them to react with one another within the vesicle interior [28].

The vesicles can be regarded as the production sites of enzymes whose information was stored in RNAs. Upon subsequent disintegration of the vesicles, these molecules were released back into the cavities, making them available again for the next cycle. It is readily apparent that the lifetime of vesicles—on the order of only a few tens of minutes—was insufficient for the development of complex molecules. Even the formation of uncoded peptides, which were newly generated with random sequences in each cycle and could assemble into membrane pores, extended vesicle lifetimes only marginally.

However, through the release of coded peptides upon vesicle breakdown, a wide variety of enzymes accumulated in the cavities over extended periods. Although flows and turbulence existed within the water-filled fracture zones, sufficient protected regions were present in which accumulation could occur. Over time, an increasing number of functional molecules thus became available and could be taken up into vesicles with each new cycle. In their presence, additional and more complex reactions became possible. At the end of each cycle, however, all components were again transferred back into the cavities. In this state, the cavities corresponded to oversized cells (“giga-cells”), albeit without a surrounding membrane.

While storage of information within vesicles was more favorable, RNA could more readily be copied within the cavities (Fig. 19). The high concentration of enzymes present there, together with the simultaneous existence of RNA strands, provided ideal conditions for the development of more complex molecules, such as the ribosome or DNA. The lifetime of this environment was on the order of millions of years.

This means that the cavities functioned simultaneously as reaction vessels and as storage sites for the building blocks of life. With each vesicle formation event, material could be drawn from the reservoir of the giga-cell, such that it was only a matter of time before a favorable mixture of functional molecules was taken up into one or more vesicles, enabling the transition to autonomous replication (Fig. 20) [29].

Fig. 19 Summary of the final steps on the path to the first cell.

Fig. 20 The decisive moment of optimal loading of a vesicle with functional molecules, followed by autonomous replication and physical division through shear forces.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

With the onset of autonomous replication through uptake of substrates from the environment via pores, and through catalytic control of molecular production, a prolonged period began during which internal processes were further developed and optimized. It presumably took several hundred million years until the cellular system had evolved to a stage at which one can speak of LUCA cells.

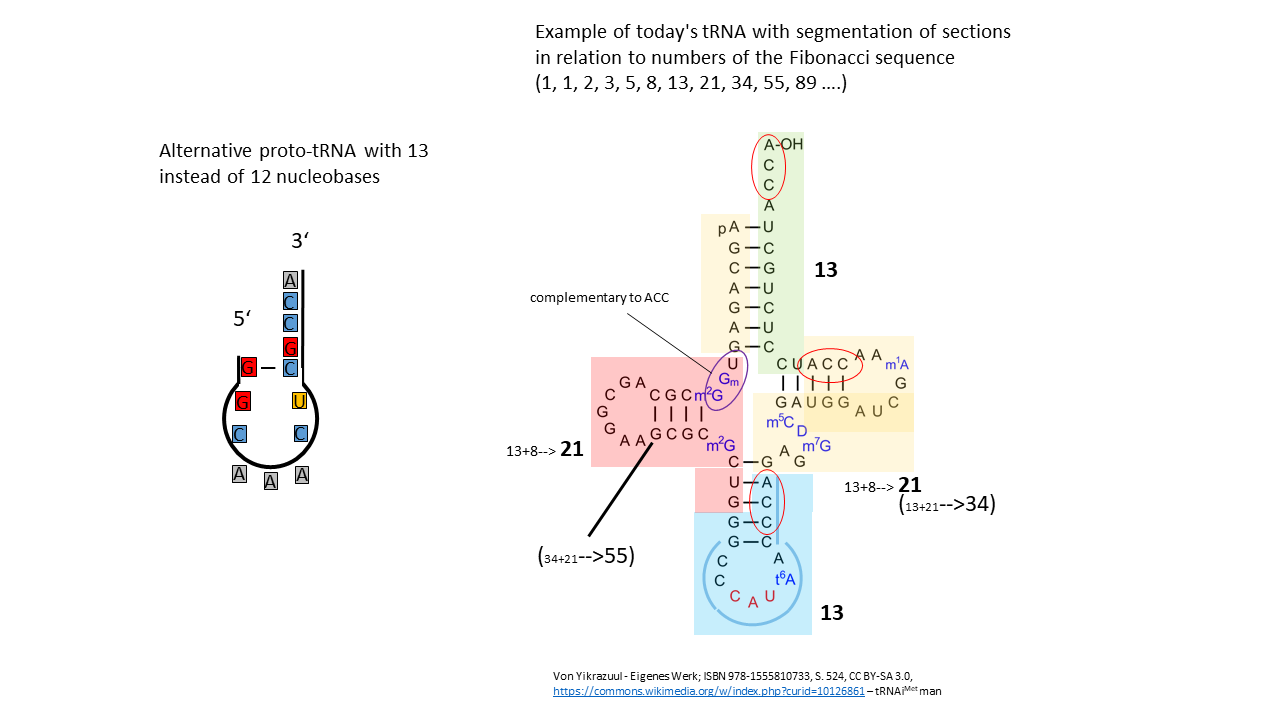

Here, an alternative proto-tRNA is presented that allows for an interesting mathematical perspective.

If the proto-tRNA described above is extended by one nucleobase, from 12 to 13, the processes of information storage outlined above can proceed in a comparable manner. It can be debated which proto-tRNA was more likely to have existed initially, the 12-base or the 13-base version. Thirteen is the seventh number in the Fibonacci sequence, a numerical pattern that is frequently observed in natural systems.

Many plant species possess flowers with a number of petals corresponding to a Fibonacci number. Likewise, the arrangement of seeds in sunflowers, pine cones, or pineapples follows two spiral directions whose counts correspond to two consecutive Fibonacci numbers. The shell of the Nautilus forms a spiral that can be approximately reproduced by the juxtaposition of squares with side lengths given by the Fibonacci numbers. The arms of spiral galaxies often follow a logarithmic spiral that can be derived from the Fibonacci sequence.

In Fig. 20-1, the alternative proto-tRNA consisting of 13 nucleobases is shown on the left. On the right, the cloverleaf representation of human tRNAMet comprising 74 bases is depicted. Assuming that a proto-tRNA with 13 nucleobases formed the basis for the evolution of contemporary tRNA, the entire strand can be subdivided into units whose numbers of bases correspond to values from the Fibonacci sequence.

Based on this observation, it may be considered whether subsequent RNA molecules, and later DNA, were constructed from modules that are related to numbers from the Fibonacci sequence. (Every fourth number in the Fibonacci sequence is divisible by 3. For example, the 16th number (987). Divided by the 3 bases of the codon, this gives 329 amino acids in a chain. This number represents three enzymes/proteins: rpoA, human cathepsin K (preproprotein), and protein 2C, a highly conserved and multifunctional protein in picornaviruses (to which the poliovirus belongs). Or the 20th number (6765) for 2255 amino acids: Parainfluenza virus 5 (strain W3) (PIV5) (Simian virus 5).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

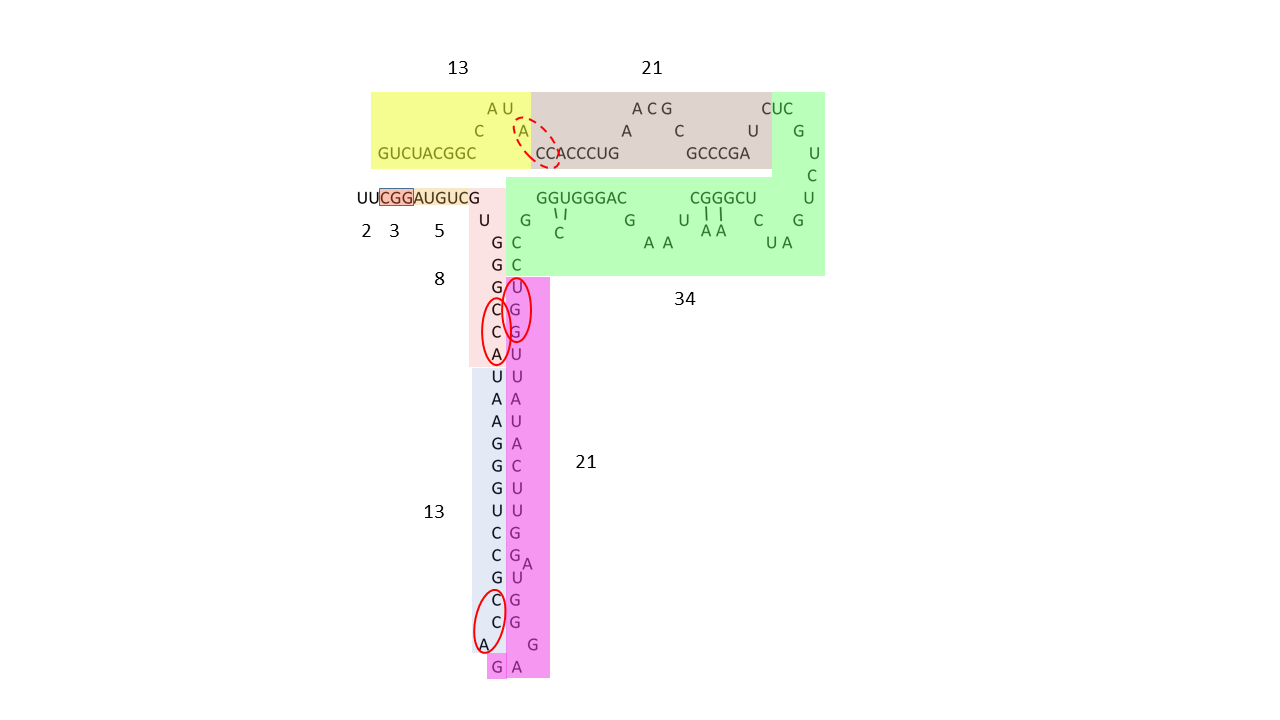

Fig. 20-1

The classification of RNA according to Fibonacci numbers is highly variable under conditions of completely unrestricted assignment and may therefore be questioned, since a large number of combinatorial possibilities exist. However, if it is assumed that two adjacent Fibonacci numbers—such as 13 and 21—must always occur contiguously within the strand, the number of possible combinations is substantially reduced. Furthermore, based on the proto-tRNA module comprising 13 nucleobases shown above, the triplet ACC or its complementary triplet UGG can frequently be positioned at the 5′ end, thereby rendering the directionality of module concatenation apparent. This, however, depends on the degree of sequence conservation. In addition, given the modular architecture, it can be expected that multiple segments that have already been formed from a given combination were subsequently linked to generate a new, longer unit. Accordingly, the present-day tRNA depicted in Fig. 20-1 could be composed of two 13/21 modules.

Example of human 5S rRNA: 08.02.2026

Fig. 20-2: 5S rRNA partitioned into modules defined by Fibonacci numbers. One module comprises a complete sequence from 2 to 34, combined with a second module of 13/21; alternatively, the segment of length 34 may be assigned to a 13/21/34 module. The dashed red ellipse indicates an ACC triplet that may originally have been located at the beginning of a module comprising 21 nucleobases and was subsequently displaced as a result of later structural rearrangements of the molecule.

— rRNA data from: Cheng, N., Mao, Y., Shi, Y., & Tao, S. (2012). Coevolution in RNA molecules driven by selective constraints: evidence from 5S rRNA.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Mirrkaryotes 29.09.2025

The previously outlined possible path to the first cell diverges at a certain point, separating the parallel development of the handedness of L-amino acids and D-ribose in the RNA of the present-day world from the alternative path involving D-amino acids and L-ribose. The question arises as to whether the development proceeded uniformly at all the numerous potential locations, or whether, after the initial expansion of the first cells from a singular origin, local conditions in other regions were so significantly altered that they led to a convergent outcome. The latter scenario appears to be the most plausible.

However, there is likely some chance that at a different site, perhaps on another small continent, a similar evolutionary path to the first cell occurred, but one that led to the opposite, mirror-image system. This would represent, alongside the life form LF1 as we currently know it, a second form, LF2. While LF1 is divided into the domains of Bacteria and Archaea (both prokaryotes), as well as Eukaryotes, LF2 could have consisted of only a single domain. The term Mirrkaryotes would be fitting for such a system.

In this context, the immediate question arises as to whether these "Mirrkaryotes" might still exist today, in inaccessible areas such as the deep biosphere, perhaps in the oldest continental cores. This leads to the crucial follow-up question: Would we be able to detect them with our current analytical methods and distinguish them from other single-celled organisms? It is possible that they have always existed alongside us, without our having taken notice of them.

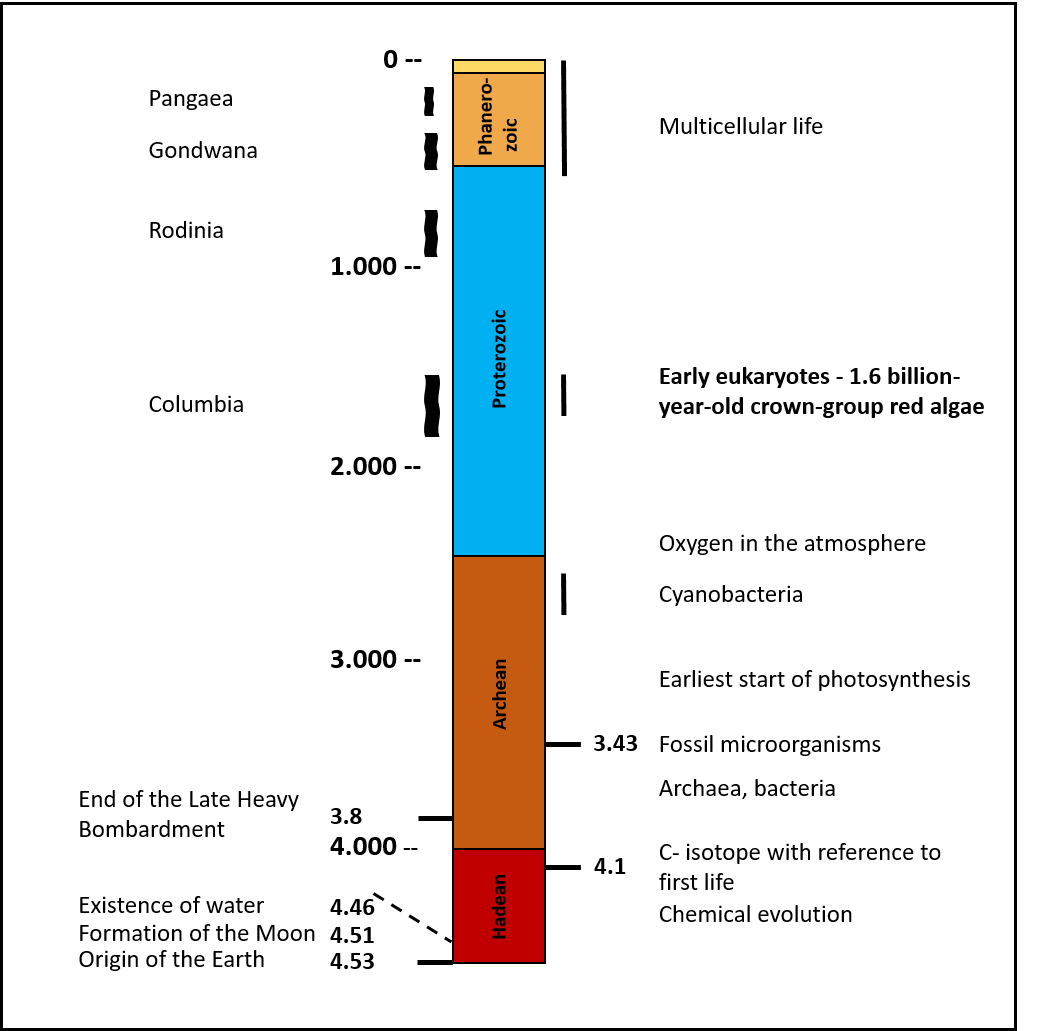

What happened next?

The geyser eruptions continuously carried organic molecules and eventually the first self-replicating cells to the surface. Consequently, "bio-films" made of organic materials must have formed in the vicinity of the exit points, in which the first cells were also embedded. However, they had little chance of surviving under the new environmental conditions. UV exposure, solar wind, lower temperatures and higher pH levels required an adaptation that took a longer period of time.

In addition, the energy and substance supply was difficult. However, the biofilm in the vicinity of the geyser probably provided the conditions for the cells to be able to absorb substances from outside. Sooner or later, climatic or regional conditions may have made it possible for the cells to survive on the earth's surface, so that they could reach the oceans via rivers. An alternative situation is conceivable for locations close to the coast, whose open fault systems lead directly into the marine environment. Entering the ocean was the decisive step that set the system of life in motion. In the ocean, the cells encountered areas that were familiar to them in terms of physicochemical conditions. It was the Black Smokers and other hydrothermal vents that provided them with unlimited, usable energy resources. At the same time, this environment again offered protection from the destructive influences that were present on the surface of the earth.

The appropriation of the submarine hydrothermal vents by the first prokaryotic cells probably led to an explosive spread of the first life form, viewed in a compressed time period. The open ocean offered ideal conditions for this with sea currents and a sufficient number of hot springs.

Long distances and unique local characteristics could lead to independent adaptations in the young family of cells, which quickly diversified as a result. This phase marked the end of the violent meteorite impacts, which mainly affected the oceans. Every major impact caused large areas of the young continents to be flooded. This was the way in which the prokaryotes were able to spread over all the large and small fragments of continental crust that had now been formed. Wherever they came into contact with hydrothermal vents on land, they could gain a foothold and continue developing.

In this context, another development on the young Earth is significant. The movement of plates began early on, which ultimately led to the shifting of the continents and subsequent collisions. What influence did this process have on the further development of the prokaryote?

The contact between differently developed cells

It is now accepted that organelles such as the mitochondria and chloroplasts of eukaryotes are derived from bacteria. There is an idea that bacteria were taken up by other prokaryotes but could not be digested. On the contrary, the absorbed bacteria continued to live in the host's cell envelope and used their metabolic products for their own sustenance. An endosymbiosis developed in which one partner lives permanently in the body of the other, like the bacteria in the intestine. The evolutionary adaptation meant that the "undigested" bacteria were gradually reduced to useful building blocks that today make a decisive contribution to the energy supply of the cell.

The eukaryotes appeared almost spontaneously on the stage of life 1.5 billion years ago. Ancestors that could be considered as transitional stages have not yet been clearly identified. 500 million years earlier, almost all existing small continents began to migrate towards one another, until a supercontinent had formed 300 million years later. It is referred to by geologists as Columbia. Its existence lasted for another 200 - 300 million years, whereby the last 100 million years were already characterized by decay and mountain building processes caused by plate tectonics. Finally, in the final phase of Columbia, the eukaryotes appeared. A billion years earlier, the concentration of oxygen in the atmosphere began to increase, to which the living world had to react.

Fig. 12 Time scale of earth evolution - Age of eukaryotes after Bengtson et al. 2017 [21]